Myth #1: Standards, without resources or mechanisms sufficient to enforce them, are adequate to respect and protect human rights in the supply chain

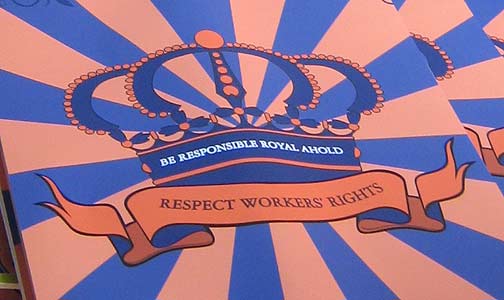

On Monday we brought you news from Ahold’s annual shareholder meeting, where the Dutch supermarket giant once again roundly — and, truth be told, a bit rudely — rejected a call by the CIW’s Lucas Benitez to join the Fair Food Program.

Just days before the shareholders’ meeting, Ahold issued a statement in response to the Campaign for Fair Food that, perhaps predictably but certainly not intentionally, did a terrific job of laying out what we are calling the Three Founding Myths of Corporate-Led Social Responsibility. Here below are those three myths, in the order in which they appeared in Ahold’s statement:

- Standards, without resources or mechanisms sufficient to enforce them, are adequate to respect and protect human rights in the supply chain;

- The market price is, by definition, a fair price;

- Corporations can be trusted to unilaterally investigate, and to determine any appropriate corrective action, when their suppliers violate their workers’ human rights.

The quizmaster approach to social responsibility…

The quizmaster approach to social responsibility…

“All of our tomato suppliers… demonstrated extensive knowledge of our standards and fully understood their requirements…”

Fully half of Ahold’s statement is dedicated to its “Standards of Engagement” and to the steps the company has taken in the three years since the CIW first brought the existence of a brutal slavery case in Ahold’s supply chain to the Dutch company’s attention back in 2010.

[Ahem… this might be your first clue to the fact that Ahold’s internal monitoring mechanisms are not, shall we say, state of the art, as it required the CIW’s intervention to bring Ahold’sattention to the watershed slavery case of US vs. Navarrete at the time.]

Here below is the relevant passage from Ahold’s statement, quoted in its entirety. Take a moment to read it closely for any description of Ahold’s mechanisms and procedures for monitoring and enforcement:

We carefully select and monitor our suppliers and require them to adhere to our Standards of Engagement, which require our suppliers to treat all employees fairly with dignity and respect, and in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations. We expect our suppliers to pay employees for all time worked and to pay wages that meet or exceed legal minimum requirements.

In response to concerns of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) about worker treatment, Ahold USA and its affiliates:

- Met with the CIW and other interested groups;

- Suspended purchasing tomatoes from the Immokalee region in 2010;

- Met with our suppliers located in the Immokalee region and resumed purchasing tomatoes only after they demonstrated their commitment to comply with our Standards of Engagement;

- Met with certain tomato suppliers again in 2011 and 2013 to monitor and reconfirm their commitment to comply with our Standards of Engagement.

All of our tomato suppliers clearly understand that all business relationships with Ahold USA and its affiliates are contingent on conduct that meets or exceeds our Standards of Engagement. They demonstrated extensive knowledge of our standards and fully understood their requirements, and the requirements of their subcontractors, to comply with them. Each of our tomato suppliers is committed to upholding our Standards of Engagement.

Let’s begin by dispensing with the two things in the passage that might pass for substantive actions:

- When Ahold says it “met with the CIW,” it was only to let us know that they had no intention, whatsoever, of signing a Fair Food agreement. We had one face-to-face meeting in New York City and, for all intents and purposes, it was over before it started.

- Ahold “suspended purchasing tomatoes from the Immokalee region” during Immokalee’s off-season, when there were no tomatoes to be purchased.

Now, those two elements aside, what’s left? Nothing but a series of meetings, once every year or two, where Ahold’s suppliers:

- “demonstrated their commitment,”

- “reconfirm(ed) their commitment,”

- “demonstrated extensive knowledge of our standards,”

- and “fully understood their requirements”

As far as anyone could possibly tell from Ahold’s own description of its monitoring process, Ahold employs a system of social responsibility by quiz, and not even a pop quiz at that. Ahold representatives apparently show up and test their suppliers’ knowledge and understanding of the company’s standards, and a passing grade signifies “commitment” to those standards.

It is a classic case of standards without the resources or procedures necessary to enforce them, in other words, of 20th century social responsibility. Ahold’s approach is mired in a past when it was sufficient for a corporation to simply declare that it has “standards of engagement,” and if it waved those standards around hard enough, sexual harassment, wage theft, and forced labor would miraculously disappear from its supply chain, like some sort of magic eraser.

Death, taxes… and human rights

Real social responsibility, however, isn’t magic.

Real social responsibility, however, isn’t magic.

It is, in a way, quite similar to taxes. No one enjoys paying taxes, even those who believe they are a necessary part of a civilized society. And so, if it were virtually impossible to get caught for cheating on taxes and, even if you were to get caught, the penalty were minimal, the vast majority of people would cheat on their taxes. There is simply no doubt about that. And that is why we as a society have created a vast apparatus of monitors, why we fund that apparatus sufficiently to do its job, and why we have established a hard and fast regime of penalties for cheating on taxes. As a result, the vast majority of people today voluntarily comply — happily or otherwise — with the tax laws (not to say there aren’t still cheaters, but that’s why we still have the IRS, because even voluntary compliance requires constant vigilance).

Real social responsibility is a grinding, day-to-day, on-the-ground job. It is a relentless battle with exploitation, abuse, and humiliation in the workplace, a gradual, incremental process with countless small victories punctuated by both regular setbacks and occasional great leaps forward. And it is achieved only by building an unbroken process of worker education, complaints, complaint investigations and resolutions, audits, corrective actions, and more audits that creates such a seamless environment of monitoring and enforcement that those who would humiliate or exploit their workers view the chance of getting caught too certain, and the cost of getting caught too high.

This relentless groundwork then leads to a true multi-stakeholder initiative, one in which willing buyers (among which Ahold cannot be counted), growers and workers have equal voices, and claims of progress are verifiable. Only then is the ideal of voluntary compliance even possible, and even then still at the cost of constant vigilance.

That is 21st century social responsibility — real, measurable, comprehensive, and driven by the people whose rights are in question, not those whose brands are in play. And that is what the Fair Food Program does, every day. To quote from the Fair Food Standards Council website:

“Under the Fair Food Program, participating growers have:

- Adopted the Fair Food Code of Conduct as their own;

- Agreed to a worker education program conducted by the CIW on company premises and company time;

- Agreed to have compliance with the program independently monitored;

- Agreed to an independent and verifiable complaint investigation and remediation mechanism in which they participate equally with the CIW and the FFSC;

- Agreed to pass on the “penny-per-pound” price premium to their workers; and

- Agreed to implement a system of health and safety volunteers which affords workers regular and structured input into the safety of their work environment.” read more

And all that is backed by the market consequences built into the CIW’s agreements with 11 multi-billion dollar retail food companies.

The times when corporations could point to a code of conduct and declare, unilaterally, that their suppliers are “committed” to that code are gone, washed away with the flood of information and analysis available today at the tap of a fingertip. The 20th century supermarket could get away with the kind of superficial attestation of compliance that Ahold so casually deployed in its statement ahead of the shareholders’ meeting. But the information age has cast a klieg light into every nook and corner of every multi-billion dollar retailer’s supply chain, from the fields of Immokalee to the factories of Foxconn, and 21st century consumers are demanding more of brands that want to earn their trust, and their business.

The standards-without-enforcement approach may help, in the short term, to protect a corporate brand. But it never was an effective way to respect and protect human rights, and it’s no longer sufficient to satisfy consumers when stories of gross human rights violations make the news. Ahold can, and must, do better than that. Ahold can, and must, embrace the highest standards of monitoring and enforcement in the industry today by joining the Fair Food Program.