[hupso title=”.@CIW prepares to cross the sea to press case for #FairFood with @AholdNews!” url=”https://ciw-online.org/blog/2015/04/ahold/”]

Action, organized in conjunction with Dutch allies, will be fifth appearance by CIW at Ahold annual meeting;

Past actions have had their controversial, educational moments…

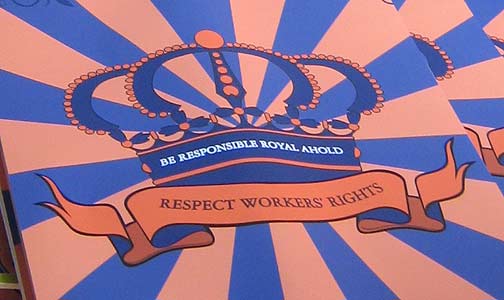

Whether it was the time the CIW’s representative was cut off as he spoke about the Fair Food Program to company directors and shareholders, or the time the chairman insisted that the CIW’s representative speak in English or not at all, Ahold’s annual shareholder meetings have never failed to highlight the differences between the directors of the European supermarket giant — parent company of the US chains Stop & Shop, Giant, Martin’s, and Peapod — and the workers who pick its tomatoes here in the United States.

And nowhere are those differences more stark than on the topic of social responsibility. Ahold’s 2013 shareholder meeting laid the debate particularly bare, prompting a four-part reflection on this site on the shortcomings of Corporate Social Responsibility entitled — clearly, if perhaps not subtly — “The three lies CEOs tell themselves about social responsibility (that only they believe), brought to you by Royal Ahold!”.

In preparation for this year’s April 15th meeting in Amsterdam, we thought we’d bring you an extended excerpt from that series, and links to all four of its parts. The clash between traditional Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the new paradigm of Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR) will be an ongoing — and perhaps definitional — battle for years to come in the fight to protect fundamental human rights in global supply chains. And the 2015 Ahold shareholder meeting will almost surely be a field on which the forces of CSR and WSR are joined once again in a struggle for the soul of social responsibility in the 21st century.

The excerpt that follows is taken from the first part in the series, entitled, “Myth #1: Standards, without resources or mechanisms sufficient to enforce them, are adequate to respect and protect human rights in the supply chain.”

… [Ahold’s statement on social responsibility] is a classic case of standards without the resources or procedures necessary to enforce them, in other words, of 20th century social responsibility. Ahold’s approach is mired in a past when it was sufficient for a corporation to simply declare that it has “standards of engagement,” and if it waved those standards around hard enough, sexual harassment, wage theft, and forced labor would miraculously disappear from its supply chain, like some sort of magic eraser.

Death, taxes… and human rights

Real social responsibility, however, isn’t magic.

It is, in a way, quite similar to taxes. No one enjoys paying taxes, even those who believe they are a necessary part of a civilized society. And so, if it were virtually impossible to get caught for cheating on taxes and, even if you were to get caught, the penalty were minimal, the vast majority of people would cheat on their taxes. There is simply no doubt about that. And that is why we as a society have created a vast apparatus of monitors, why we fund that apparatus sufficiently to do its job, and why we have established a hard and fast regime of penalties for cheating on taxes. As a result, the vast majority of people today voluntarily comply — happily or otherwise — with the tax laws (not to say there aren’t still cheaters, but that’s why we still have the IRS, because even voluntary compliance requires constant vigilance).

Real social responsibility is a grinding, day-to-day, on-the-ground job. It is a relentless battle with exploitation, abuse, and humiliation in the workplace, a gradual, incremental process with countless small victories punctuated by both regular setbacks and occasional great leaps forward. And it is achieved only by building an unbroken process of worker education, complaints, complaint investigations and resolutions, audits, corrective actions, and more audits that creates such a seamless environment of monitoring and enforcement that those who would humiliate or exploit their workers view the chance of getting caught too certain, and the cost of getting caught too high.

This relentless groundwork then leads to a true multi-stakeholder initiative, one in which willing buyers (among which Ahold cannot be counted), growers and workers have equal voices, and claims of progress are verifiable. Only then is the ideal of voluntary compliance even possible, and even then still at the cost of constant vigilance.

That is 21st century social responsibility — real, measurable, comprehensive, and driven by the people whose rights are in question, not those whose brands are in play. And that is what the Fair Food Program does, every day. To quote from the Fair Food Standards Council website:

“Under the Fair Food Program, participating growers have:

- Adopted the Fair Food Code of Conduct as their own;

- Agreed to a worker education program conducted by the CIW on company premises and company time;

- Agreed to have compliance with the program independently monitored;

- Agreed to an independent and verifiable complaint investigation and remediation mechanism in which they participate equally with the CIW and the FFSC;

- Agreed to pass on the “penny-per-pound” price premium to their workers; and

- Agreed to implement a system of health and safety volunteers which affords workers regular and structured input into the safety of their work environment.” read more

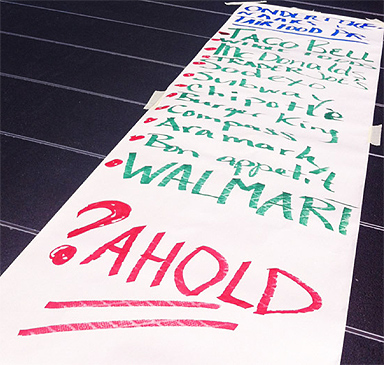

And all that is backed by the market consequences built into the CIW’s agreements with 11 multi-billion dollar retail food companies.

The times when corporations could point to a code of conduct and declare, unilaterally, that their suppliers are “committed” to that code are gone, washed away with the flood of information and analysis available today at the tap of a fingertip. The 20th century supermarket could get away with the kind of superficial attestation of compliance that Ahold so casually deployed in its statement ahead of the shareholders’ meeting. But the information age has cast a klieg light into every nook and corner of every multi-billion dollar retailer’s supply chain, from the fields of Immokalee to the factories of Foxconn, and 21st century consumers are demanding more of brands that want to earn their trust, and their business.

The standards-without-enforcement approach may help, in the short term, to protect a corporate brand. But it never was an effective way to respect and protect human rights, and it’s no longer sufficient to satisfy consumers when stories of gross human rights violations make the news. Ahold can, and must, do better than that. Ahold can, and must, embrace the highest standards of monitoring and enforcement in the industry today by joining the Fair Food Program.

Check back soon for news from the CIW’s visit to Ahold’s 2015 shareholder meeting in Amsterdam. While this will be the fifth such meeting that the CIW has attended, with no discernible change in Ahold’s position toward the Fair Food Program, hope, like Amsterdam’s famed tulips, springs eternal. Last year, after Walmart signed a groundbreaking Fair Food agreement, Ahold issued a new statement containing the smallest of shifts in language. See the bolded sentences below:

Ahold USA is committed to paying a fair market price for tomatoes from Florida suppliers, but Ahold USA does not directly negotiate wages with our suppliers’ employees. However, we have taken note of recent developments in the way that CIW is reaching agreements. We will review and discuss this with the relevant food industry trade associations as well as our suppliers.

Who knows, exactly, what those words meant to Ahold when they issued their statement ahead of last year’s annual meeting on April 15, 2014. Perhaps we shall find out more this year. But in the meantime, we leave you with the links to all four posts of the 2013 series, in order, for you continued reflection:

- The three lies CEOs tell themselves about social responsibility (that only they believe), brought to you by Royal Ahold!

- The three founding myths of corporate-led social responsibility: Myth #1: Standards, without resources or mechanisms sufficient to enforce them, are adequate to respect and protect human rights in the supply chain…

- Myth #2: The market price, by definition, is a “fair price”…

- Myth #3: Corporations can be trusted to investigate, and to determine any appropriate corrective action, when their suppliers violate their workers’ human rights.