Bowing to farmworker and consumer pressure, Wendy’s declares intention to bring tomato purchases back to U.S. “by the end of the year” in surprise announcement at annual shareholder meeting in Dublin, Ohio!

Company stops short, however, of joining award-winning Fair Food Program, instead shifts purchases to greenhouse operations outside the FFP and professes blind faith in failed third-party audits…

This past Tuesday, Wendy’s corporate executives and board members gathered at the company’s headquarters in Dublin, Ohio, for the fast-food giant’s annual shareholder meeting. As the cool and rainy spring day dawned, nearly three dozen representatives of the Fair Food Nation headed into the meeting, equipped with hard questions for CEO Todd Penegor and Board Chair Nelson Peltz on the company’s unconscionable decision to purchase the vast majority of its tomatoes from Mexico’s famously brutal produce industry. Meanwhile, outside the meeting, nearly 200 supporters — farmworkers and consumers alike — filled the sidewalk in a spirited picket, their chants echoing off the surrounding buildings.

All the pieces were in place for what would turn out to be a truly memorable day. It was a day on which, for the first time, a major US retail food company repatriated its tomato purchases from Mexico in response to intense scrutiny of the horrific labor conditions in that country. And yet, despite this historic news, it was a day on which Wendy’s nonetheless disappointed its critics by announcing that it would sidestep Fair Food Program farms and purchase exclusively from greenhouse growers outside the program, relying on discredited, for-profit auditing firms to monitor conditions at its new suppliers’ operations. At the end of the day, Wendy’s move left the burger chain awkwardly akimbo, one foot squarely on the right path, the other still firmly stuck in the past.

Today, we bring you the initial report from both outside and inside the 2018 Annual Shareholder meeting, with more analysis to come in the days ahead. There’s a lot of ground to cover, so we’ll jump right in!

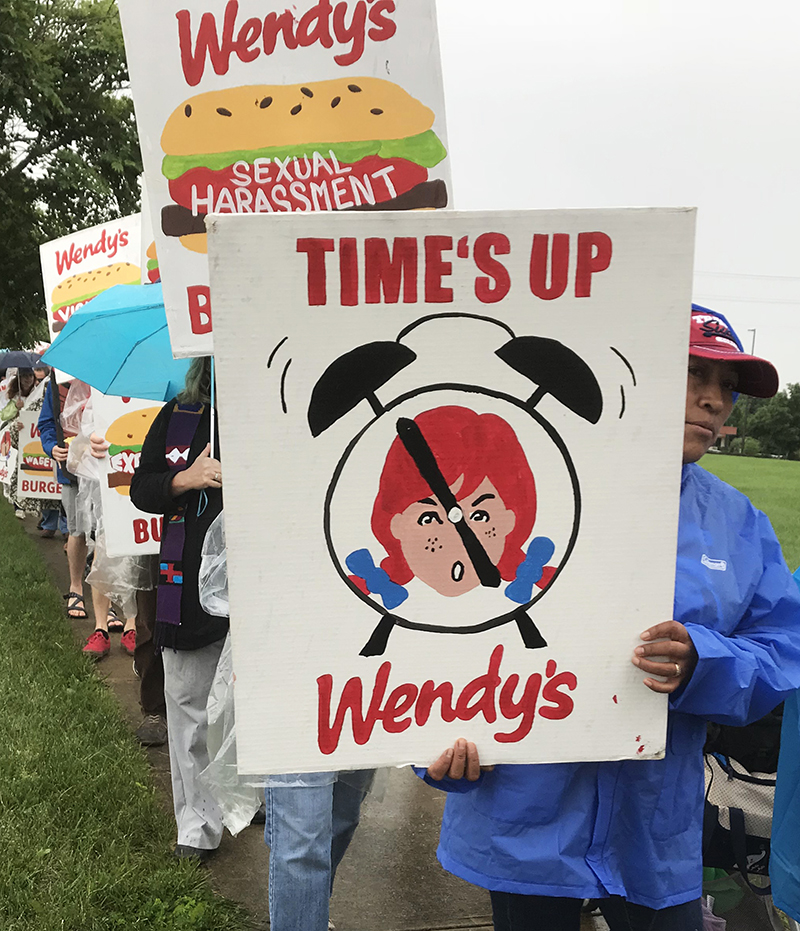

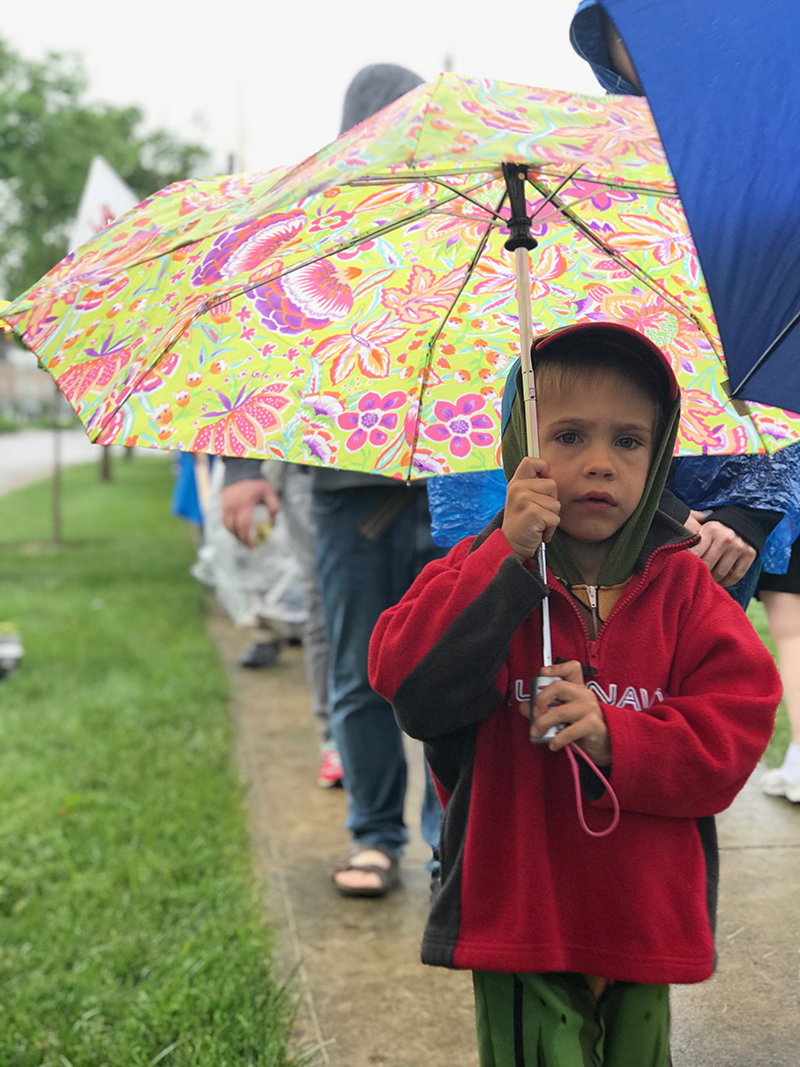

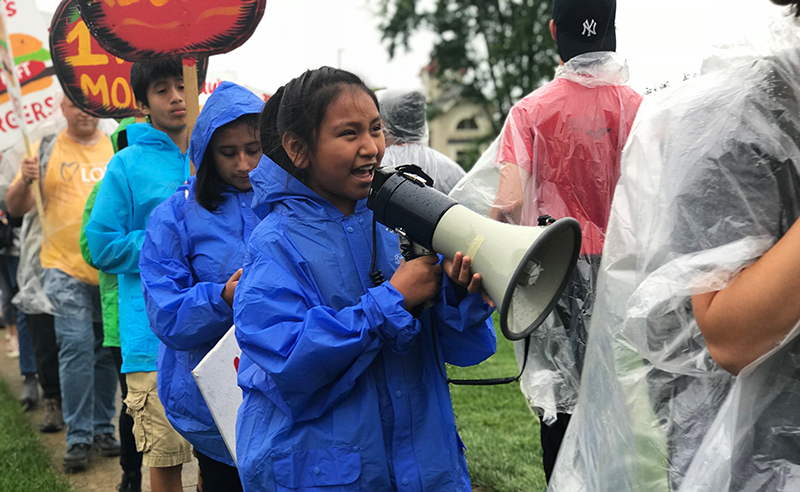

Outside the meeting: “Your burgers may be square, but your food ain’t fair…!”

Outside of the meeting, nearly 200 protesters marched and chanted in spite of a steady, driving rain.

Over 50 farmworkers and their families departed Immokalee on Sunday evening and headed to Ohio. They arrived nearly 24 hours later, rested and ready for the protest early Tuesday morning. They were joined there by a joyous crowd of Fair Food allies not only from the Columbus area, but from across the Midwest!

Faith leaders and community members joining the Immokalee crew hailed from a wide range of traditions. Columbus-area Unitarian Universalists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Quakers, United Methodists, and rabbis chanted and cheered alongside local community leaders including representatives from the Ohio Poor People’s Campaign, Local Matters, the Inter-Religious Task Force on Central America, and the Black Queer & Intersectional Columbus. Of course, the ever-energetic crew from Workers’ Dignity in Nashville drove up, bucket drums in hand. And last, but by no means least, students and young people came out in force, streaming into Dublin from Fair Food strongholds including the University of Michigan, Ohio State University, and the Methodist Theological School in Ohio.

Inside the shareholder meeting: “In light of the documented failure of voluntary auditing schemes, why does Wendy’s believe these schemes can adequately protect workers and Wendy’s corporate reputation?…”

Inside the shareholder meeting, Fair Food Nation representatives — including half a dozen farmworkers from Immokalee — prepared to grill Wendy’s executives on the company’s longstanding refusal to protect workers’ human rights in its supply chain by joining the Fair Food Program. But before the Question & Answer session could begin, the company’s Chief Communications Officer, Liliana Esposito, kicked off the meeting with a special presentation.

And just what was the hamburger giant’s big reveal (an announcement so important that Wendy’s apparently fed the Wall Street Journal the exclusive story, which the Journal released just minutes ahead of the meeting itself)? Was it record sales figures? Nope. New meal ideas? Nope. A bold marketing initiative? Nope.

Rather, Ms. Esposito focused the shareholder meeting spotlight squarely on… the humble tomato, a minor ingredient in the company’s extensive meal offerings, but an ingredient rendered exceptionally important to the company’s brand reputation due to relentless pressure from the Fair Food Nation. “Working with about a dozen suppliers, the vast majority of our tomatoes, by year end, by early next year, will come from the United States and Canada,” Ms. Esposito announced. She then went on to give some revealing context to the decision, offering something of an olive branch to CIW and its many supporters:

… We know that there are individuals associated with CIW and other associated organizations here today. You have long focused on working conditions for tomato workers. We appreciate that concern, we share it, and we are thrilled to support this higher level of comfort and safety for workers in greenhouse farms.

The announcement shocked the room and forced the Fair Food Nation representatives to pivot their questions in real time from focusing on Mexico to probing the details of Wendy’s new purchasing policy.

Following the opening presentation, it was time for Board Chairman Nelson Peltz and CEO Todd Penegor to take questions from the audience. After several questions on topics not related to the Fair Food Program, Mr. Peltz called on the CIW’s Gerardo Reyes Chavez. Gerardo proceeded to describe the many concrete changes brought about by the Fair Food Program, the widespread praise it has earned from the United Nations to the White House, and the many elements that make the Program so uniquely effective among social responsibility initiatives.

Then, responding to the news of Wendy’s abrupt shift away from Mexican tomatoes, Gerardo concluded:

I’m glad to hear the announcement that was given about the intention of changing suppliers, but I am afraid that it is not enough. Changing suppliers to another place where there is still no system to guarantee that the workers are receiving the dignified treatment that they deserve when producing tomatoes for Wendy’s is not enough… My question is for Mr. Penegor and Ms. Esposito: how can you demonstrate that your Code of Conduct is effectively addressing and eliminating child labor, sexual violence, and forced labor in your supply chain? How can you tell your investors that you’re doing the right thing by this with systems that you said you have?

Mr. Penegor – after commending the CIW on its work “in the Immokalee region of Florida” (a somewhat grudging acknowledgement, as he is surely well aware that the Fair Food Program extends to seven states and three crops, covering tens of thousands of farmworkers) – emphatically defended the company’s “great supply partners” and its supplier code of conduct.

When Gerardo pressed him further on Wendy’s continued refusal to join the Fair Food Program despite returning its purchases to the US, Mr. Penegor said that the company already works with several auditing firms, including SA8000 (a set of ethical supply chain standards administered by Social Accountability International) and SMETA (similarly, a certification scheme monitoring many types of globally sourced products), adding “those are audits that are all acceptable where we source our product today.”

Fortunately for those in attendance, there was an expert on SA8000 and SMETA in the room, and that expert – Laura Gutierrez of the Worker Rights Consortium – got her own turn at the mic.

Ms. Gutierrez explained that, as an independent factory monitor, the Worker Rights Consortium has witnessed first-hand how voluntary factory inspection programs like those carried out by SA8000 and SMETA have failed, time and again, to protect workers, and described the tragic consequences of those failures. Her statement and question for the fast food executives were so powerful that we are including them here in full:

Programs like the SA8000 and SMETA schemes used by Wendy’s produce an endless parade of factory audits, officially measuring compliance with companies’ standards. What these programs lack, however, is the essential element of independent enforcement.

Recent garment industry tragedies demonstrate that standards without enforcement cannot safeguard workers. The collapse of Rana Plaza, which killed more than eleven hundred young Bangladeshis in 2013, is the most notorious disaster in the South Asian garment industry, but by no means the first. A series of fires and building collapses killed hundreds in the years prior to Rana.

In virtually every case, the factory had been inspected under these same, or very similar, voluntary audit programs, but they failed to address the hazards that were taking workers’ lives. In 2012, a Pakistani factory called Ali Enterprises was certified by SA8000 auditors. Mere weeks later, a fire killed nearly 300 workers. They could not escape because Ali Enterprises didn’t have fire doors.

These catastrophes teach a profound lesson: it is not enough to subject workplaces to an inspection program. The program must be enforceable and include genuine worker participation. None of the voluntary schemes in the garment sector provided worker representatives with the enforcement power necessary to hold the factories and brands accountable. So they failed. Workers died.

In the wake of the Rana Plaza catastrophe, over 220 brands signed a binding safety agreement with worker representatives, because they recognized that voluntary auditing schemes exposed them to unacceptable reputational risk. The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh has radically reduced the chances that a Bangladeshi worker will die producing garments – the same kind of sweeping risk reduction the Fair Food Program has achieved in agriculture on sexual harassment, wage theft and other issues.

In light of the documented failure of voluntary auditing schemes, why does Wendy’s believe these schemes can adequately protect workers and Wendy’s corporate reputation?

Mr. Penegor responded that he was confident in Wendy’s “long-term relationships” with suppliers, and that those partners understood that they “will not be suppliers to Wendy’s if they can’t live up to that supplier code of conduct, including human rights.” He went on to assure the audience that “it’s not just independent audits” that protect their supply chain, but that Wendy’s own quality control departments head out to suppliers’ operations so they can “see it with our own eyes and ears.”

Laura repeated, for emphasis, that “in nearly every single factory disaster that happened in South Asia, in just the last couple years, factory auditors like the ones you mentioned had been there mere weeks before factory fires and building collapses had killed thousands of workers.” Mildly, Mr. Penegor repeated that they were “absolutely comfortable” with their supply base, because “quality is our recipe, and we need to make sure we live up to that high standard.”

A victory for farmworkers and consumers, but a partial one, with more remaining to be done…

Needless to say, Tuesday’s shareholder meeting was far too eventful to pack a full recounting and analysis into one post. In the coming days, we will be unpacking the significance of Wendy’s decision, providing additional context, press round-ups, and next steps in the Campaign for Fair Food. For now, we want to share three key takeaways:

1. Wendy’s decision to move over 90% of its tomato purchases to the U.S. is a significant victory for the broader movement to improve conditions for tens of thousands of workers in both the United States and Mexico.

Wendy’s announcement today is a victory, if only a partial one, for farmworkers and consumers demanding respect for human rights in Wendy’s supply chain. Purchasing almost exclusively from Mexico was never sustainable given the documented crisis of violence, corruption and impunity there, and Wendy’s shift of purchases back to the United States is definitely a step in the right direction.

Under the intense spotlight of the Campaign for Fair Food, Wendy’s hollow claims of social responsibility in Mexico wilted. This is a victory for the farmworkers who have courageously spoken out about the sexual harassment, physical violence, and extreme poverty they personally faced while harvesting in Mexico’s fields; for the determined journalists who have labored fearlessly to expose conditions in Mexico’s produce industry; and for the consumers who ensured that Wendy’s understood that its customers value not only high quality, but also transparency and human rights. It seems the campaign moved Wendy’s to truly examine its supply chain for the first time, and to their credit Wendy’s leaders determined that purchasing from Mexico was not a viable response to consumers calling on the company to join the Fair Food Program.

All major produce buyers currently purchasing produce in Mexico should take heed of Wendy’s decision. Doing business with exploitative growers will only result in more exploitation. Conditions will only improve in Mexico when growers there see demand shifting away from their fields and towards growers who respect their workers’ fundamental human rights.

2. Wendy’s still has work to do before it lives up to its promises to value the lives and human rights of farmworkers.

Now that Wendy’s has taken the first necessary step of repatriating its tomato purchases, it is time for the company to complete the process by joining the Fair Food Program, the widely-recognized gold standard of social responsibility. Until they do, today’s news will remain a half measure. The few greenhouse growers that exist today are not part of the FFP, and so there is simply no way their workers can enjoy the high bar of human rights protections that workers on FFP farms enjoy. Indeed, recent reports out of Canada, where Wendy’s indicated it would likely purchase a small percentage of its tomatoes, confirm that greenhouse workers there, and farmworkers generally, face many of the same abuses — including sexual violence and forced labor — that workers outside the Fair Food Program continue to face here in the U.S.

And it isn’t just Canada. The CIW’s Lupe Gonzalo and Nely Rodriguez — two farmworker women leaders who were notably not called on during the meeting — hammered this point home following the shareholder meeting. In Nely’s words, “We have received complaints that greenhouse workers are very isolated, and sometimes, there is even greater risk for sexual abuse on the supervisors’ part because there are fewer workers there.”

Lupe added, “The reality is that workers in greenhouses face the very same situations of abuse, and sometimes its even worse than in an open field. Sometimes, people think of greenhouses in the way they think about organic food — the tomato sounds like it will be of a higher quality, and so the working conditions must also be better. But it’s not just about having organic food on the table, or even just about saying that workers have shade and therefore all of their problems are solved — it’s about ensuring actual human rights. But Wendy’s isn’t going to see or understand that, because they once again are sitting inside in their offices, dreaming up the quality of life that farmworkers supposedly have.”

3. Wendy’s continues to invest in the long-discredited model of audits that lack worker participation and binding enforcement.

Wendy’s reliance on standards and auditing programs such as SA8000 and SMETA is, at best, woefully misguided. Even a cursory examination of SA8000 reveals that the widely-criticized program certifies exactly zero tomato farms in the United States. Moreover, it has certified one, and only one, in Mexico: none other than Bioparques de Occidente. Readers of this site will remember Bioparques as the massive Mexican agribusiness that found itself at the heart of the the LA Times’ shocking exposé of the horrific conditions – including a brutal case of forced labor – faced by farmworkers in Mexico’s produce industry.

To say, therefore, that these certification schemes are adequate, much roughly equivalent to the Fair Food Program, is nothing short of absurd.

We’ll give the last word in today’s post to Nely, who reminded allies and workers — many of whom have been working side by side for years in the Wendy’s Boycott — that Tuesday’s meeting marked a significant moment in the campaign: “Wendy’s is feeling the pressure built by the incredible work we are doing. Together, we know that we will ultimately bring them into the Fair Food Program.”

Stay tuned for more on the shareholder meeting in the week ahead!