Levi Strauss & Co, the Children’s Place, and Kontoor Brands sign “legally-binding WSR agreement… to address long-standing issues of sexual harassment and gender-based violence in the[ir] Lesotho-based suppliers”;

New Lesotho program “modeled after the Fair Food Program’s approach to combating sexual harassment and… will feature an independent complaint body similar to the Fair Food Standards Council”;

Latest victory demonstrates power of collaboration through burgeoning WSR Network to spread real, worker-led human rights protections in global supply chains!

First, the facts. Here’s an excerpt from a statement on the landmark agreement from Workers Rights Consortium (WRC), one of several US-based organizations that facilitated the years-long process that led to the agreement in Lesotho (and one of the founding members of the WSR Network):

Last Thursday marked the announcement of a set of landmark agreements among leading apparel brands, a coalition of labor unions and women’s rights advocates, and a major apparel supplier to combat gender-based violence and harassment in Lesotho’s garment sector. These enforceable agreements—with Levi Strauss & Co., The Children’s Place, and Kontoor Brands—link each of the brands’ ongoing business with the supplier, Nien Hsing Textile Co., to the supplier’s acceptance of and cooperation with a worker-led program to eliminate sexual harassment and abuse. The program features an independent complaint investigation body with the power to direct punishment of abusive managers and supervisors, up to and including dismissal.

This program arises from years of worker organizing at Nien Hsing by the Independent Democratic Union of Lesotho (IDUL), United Textile Employees (UNITE), the National Clothing Textile and Allied Workers Union—and from years of women’s rights advocacy by the Federation of Women Lawyers in Lesotho and Women (FIDA) and Law in Southern African Research and Education Trust-Lesotho (WLSA). Read more >>

It is an inspiring story of how workers in an industry long distinguished for extreme exploitation found a way to harness the purchasing power of some of the most powerful brands in the apparel industry to monitor and enforce their own rights — in particular the right to work free of sexual harassment and assault — in the workplace.

You can read more about that story in the New York Times (“Report: Levi’s, Wrangler, Lee Seamstresses Harassed, Abused”) and in the Guardian of London (“Bosses force female workers making jeans for Levis and Wrangler into sex”).

Behind every great story is a backstory…

But the backstory of how apparel factories in Lesotho became the very latest front in the expansion of the WSR model – an all-too-rare success story of collaboration among multiple organizations across borders and across industries to advance workers’ fundamental human rights – is quite interesting in its own right.

The WRC, which exposed the abuses and worked with an international coalition that supported the workers in Lesotho throughout the process that resulted in the agreement, released a second statement on the history that led up to last week’s announcement. The statement set out to “explain the roles of the organizations that have contributed to this breakthrough; contrast the new binding agreements and the program they will create with voluntary industry labor codes that consistently fail to protect workers; and provide comment on several key aspects of the agreement and their significance.” You can find the statement in its entirety here.

Of course, first and foremost in that explanation was the tireless – and fearless – organizing of the many unions and women’s organizations in Lesotho themselves. The statement reads:

The agreements would not have come about without years of courageous organizing by the three unions representing garment workers at the supplier, Nien Hsing Textile, one of the world’s largest denim clothing manufacturers. The Independent Democratic Union of Lesotho (IDUL), the United Textile Employees (UNITE), and the National Clothing Textile and Allied Workers Union (NACTWU) managed to survive and build membership–despite retaliatory firings of union activists, threats to fire the entire workforce if the unions persisted in their organizing, discrimination against union members (including denial of the opportunity to earn overtime pay), denial of the right of members to be represented by the union in disciplinary proceedings, and other violations of associational rights… Had they not persevered across years of hostility and reprisals, it is likely the gender-based violence and harassment at these factories might never have been exposed. Instead, the unions survived, helped the WRC document and expose the reality facing women workers in the factories, and then represented workers ably in the negotiations that followed with the brands and the employer.

Equally important in achieving these agreements were the Federation of Women Lawyers in Lesotho (FIDA) and Women and Law in Southern African Research and Education Trust-Lesotho (WLSA), the country’s leading women’s rights advocates. WLSA and FIDA have been fighting gender-based violence in Lesotho for three decades, achieving concrete progress via political and legislative advocacy (including passage of the national Sexual Offences Act of 2003 and the Child Protection and Welfare Act of 2011), while also providing vital counseling and legal support to victims. WLSA and FIDA joined with the three unions to battle workplace harassment and abuse at the factories and to negotiate with the brands and Nien Hsing. Their insights were indispensable in the design of the anti-sexual harassment program the new agreements will create.

It then goes on to note the roles of several of the international workers’ rights organizations in the ongoing support of the workers’ in Lesotho throughout the extended negotiation and strategic development process:

The WRC is proud to have contributed to this breakthrough. It was clear from the early days of our investigation at Nien Hsing’s Lesotho factories that the abuses women workers were facing were both egregious and extensive – and that nothing short of a comprehensive program to combat these abuses, backed by enforceable contracts with brands and the employer, could change the culture of these workplaces. We recommended to the unions and women’s rights organizations that they join forces and pursue such agreements. We conveyed our findings to the brands and pressed them to agree to enter negotiations. We worked with the Lesotho leaders, and with the US organizations whose roles are outlined below, to design the program that these new agreements will put place – with particular emphasis on governance structures and enforcement provisions, for which we drew on our experience helping to create and implement the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. We worked with all of the parties through nine months of negotiations to help secure strong agreements and we will now support all of the parties as implementation begins.

Along with the WRC, two other US organizations worked side-by-side with the Lesotho leaders in the negotiation process and made contributions pivotal to their successful outcome. The Solidarity Center, the largest US-based organization working on labor rights globally, has a long history of partnering with unions in Lesotho and across southern Africa and deep experience and knowledge on the issue of gender-based violence in global manufacturing supply chains. The Solidarity Center’s technical expertise, and its passionate advocacy for worker empowerment as the only viable means to combat gender-based violence in the workplace, were critical factors in the negotiation. Workers United, which represents workers in the apparel industry in the US, has a longstanding collective bargaining relationship with Levi Strauss & Company, and brought decades of negotiating experience to the table with the three brands and to subsequent negotiations with Nien Hsing. Workers United was a catalyst of the rejuvenated anti-sweatshop movement that emerged in the US in the late 1990s and the vital support the union has provided the Lesotho leaders continues a long tradition of international solidarity.

And last, but not least, the WRC statement talks about the “foundational” role played by the CIW, the Fair Food Standards Council, and the WSR-Network:

There is another group of organizations in the US whose work was foundational to this breakthrough – the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), the Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC) and the Worker-driven Social Responsibility Network (WSR-N). CIW’s Fair Food Program (FFP) is built on binding labor rights agreements among major food brands, agricultural producers, and CIW – a worker-based human rights group that has been organizing, and advocating on behalf of, migrant agricultural workers in the US since 1993. The FFP’s extraordinary success in combating sexual harassment in Florida’s tomato fields – where abuses were widespread, severe and deeply ingrained – is one of the most inspiring labor rights success stories of this decade. The program the Lesotho agreements will create is modeled after the FFP’s approach to combating sexual harassment and the program will feature an independent complaint body similar to the Fair Food Standards Council, which investigates complaints under the FFP.

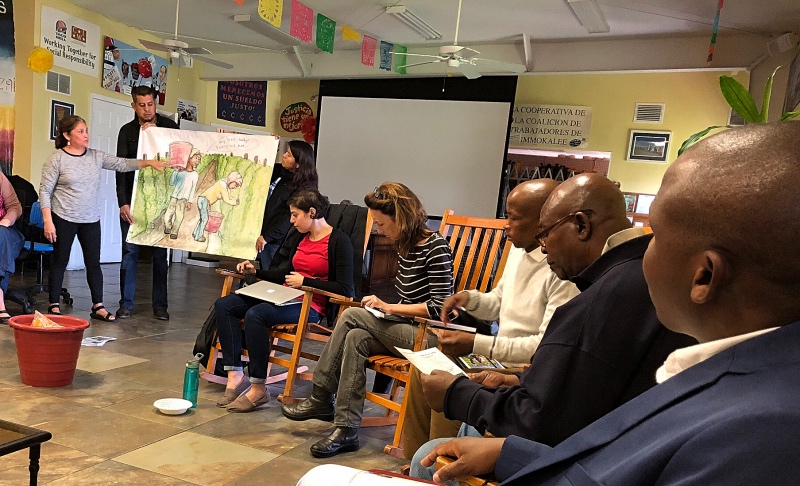

In addition to providing a real-world example of how gender-based workplace violence can be eradicated in even the most challenging labor rights environments, CIW and the FFSC provided practical and strategic guidance to the Lesotho leaders during the negotiation process. They were aided, in this regard, by the WSR-N, a network of worker organizations and labor rights advocates that promotes and supports efforts to establish enforceable agreements between global brands and worker representatives – like the FFP, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, and these new agreements in Lesotho. The WSR-N facilitated a trip for the Lesotho leaders, early in the negotiation process, to meet with CIW and with WRC, the Solidarity Center, and Workers United. The Lesotho leaders view these meetings as a key juncture on their path. As the Lesotho organizations begin implementation of the agreements, CIW and the FFSC will be an important part of the implementation team, providing practical experience with key aspects of the program that is unavailable from any other source.

Success has many mothers, and fathers…

Clearly, the extraordinary news out of Lesotho this week would not have been possible without an extraordinary struggle, and an equally extraordinary collaboration among a wide range of worker and human rights organizations in support of that struggle. It is news that we are proud to be a part of, and we look forward to continuing to contribute to the implementation and development of a program that will bring long-overdue justice to more than 10,000 workers in southern Africa.

It is truly remarkable to contemplate the broader meaning of this moment, and perhaps sometime soon we will take a deeper dive into the significance of this latest front in the global expansion of the WSR model.

But for now, just consider this: Some of the poorest, least powerful workers in this country – farmworkers divided by language, nationality and ethnicity, immigrant workers in a country itself deeply divided about their presence and contribution here – managed somehow over the course of two decades of struggle to forge a new form of worker power, a new paradigm for protecting vulnerable workers’ fundamental human rights at the bottom of global supply chains. Worker-driven Social Responsibility, that new paradigm, emerged fully formed for the first time in Immokalee, a dusty, dirt-poor, crossroads town at the top of the Everglades that just a few years ago was dubbed “ground zero for modern-day slavery” by federal prosecutors. A more unlikely birthplace for, in WRC’s words, “one of the most inspiring labor rights success stories of this decade” – or as it was put in a different moment in the pages of the Washington Post, “one of the great human rights success stories of our day” – would be hard to imagine.

Yet today, that battle to end forced labor, sexual assault, violence against workers and so many more abuses in Florida’s fields has not only spread up the East Coast, into new crops and new industries, and is continuing to build out across this country, but it is now inspiring workers from across oceans to marshal the same forces and build the same structures to monitor and enforce their own rights in vastly different industries.

The WSR model, and the growing WSR Network dedicated to its expansion, is indeed, to borrow the words of another observer from another moment in this movement’s remarkable history, “a visionary strategy… with potential to transform workplace environments across the global supply chain.” And this week’s news out of Lesotho is only the latest example of that potential becoming reality.