|

UPDATE #2: October 16, 2011

Center for Constitutional Rights, RFK Center for Justice and Human Rights, National Economic and Social Rights Institute issue open letter; Oxfam America condemns suits… As more people learn of the Florida Legal Services (FLS) lawsuits against the fast-food companies participating in the CIW’s Fair Food Program, the criticism — on both the legal merits of the suits and their potential social and economic impacts on farmworkers — continues to grow. Last week, three widely-respected legal and human rights organizations — the Center for Constitutional Rights, the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, and the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative — issued a public letter to FLS Executive Director Kent Spuhler condemning the lawsuits. Since the letter’s publication, several prominent labor law professors have added their names to the list of signatories. Here is its conclusion:

Meanwhile, Oxfam America has weighed in on the lawsuits as well. In a letter to the members of the CIW, Minor Sinclair, Director of the US Regional Office, writes:

Stay tuned as reaction to the lawsuits continues to evolve. ****************** UPDATE: September 30, 2011

Since we wrote the Special Comment that follows this update, the Florida Legal Services (FLS) lawsuit has come under closer scrutiny in the press. And it has not fared well. In an editorial entitled, “Fair pay program honorable” (9/30/11), the Ft. Myers News-Press sets the record straight on claims made in the lawsuit and on other statements made by FLS representatives about the Fair Food Program. Here are some of the highlights (emphasis added):

There’s much more, we just don’t have the space here to excerpt it all. But we urge you to read it, which you can do here. The editorial does an excellent job of debunking virtually all of Florida Legal Services’ claims. There is one claim, however, which needs further clarification. The editorial goes on to say:

That’s half right. It is true that the CIW’s agreements with the nine multi-billion dollar food companies are confidential. That is because those agreements contain proprietary information about the structure and function of the companies’ individual supply chains, and billion dollar companies are not in the habit of sharing that kind of information. In fact, if that information had to be divulged, it would probably be impossible to bring new corporations into the Fair Food Program. Companies would be unlikely to share the extremely sensitive data required to ensure accountability, as their trust in the system would be lost.

Fact: The information contained in those agreements about workers’ rights — about the Fair Food Code of Conduct, including the penny-per-pound bonus and all the new standards for a more humane workplace that it establishes — is not confidential. In fact, it’s probably the least confidential thing in the tomato industry today. Over the past season, during which the Fair Food Program was piloted on five farms, over five thousand workers received face-to-face, worker-to-worker education on exactly those new protections. And they received that education on the clock. This coming season, as the Fair Food Program begins full implementation throughout the Florida tomato industry, well over 30,000 workers will receive that same information. Workers have been, and will continue to be, made aware of their rights through the multi-faceted approach developed during last season’s pilot program, including:

So, to accuse the Fair Food Program of somehow keeping workers in the dark about their rights under the program is worse than wrong, it’s scurrilous. This is especially so given that the CIW’s worker-to-worker education program — which, by the way, is a true rarity in the world of social responsibility– is hardly a secret. For example, FLS might have seen this article, by Tomatoland author Barry Estabrook, “Estabrook Goes to Tomato School and Learns about the New Rights Farmworkers Have Won under the CIW Fair Food Agreement,” posted on our website earlier this year. [In fact, it’s probably worth pausing for a moment to reflect on the remarkable title of that article — “Estabrook Goes to Tomato School and Learns about the New Rights Farmworkers Have Won under the CIW Fair Food Agreement” — in light of the FLS intimation that there’s some sort of effort afoot to shield workers from their rights under the Fair Food Program…] Or, they might have found a description of the education program and other changes brought about by the Fair Food Program last season on this highly visited page (scroll down to the section entitled, “Change is underway”). Or noticed its top billing in the press release announcing the CIW’s agreement with the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange. Or they might have simply asked us before making wildly false accusations. But they never did. You are free to draw your own conclusions as to why. |

![]()

Special Comment on the Florida Legal Services Lawsuit

Many of you may have already read coverage of a lawsuit filed against Burger King this week in Miami questioning the payment of penny-per-pound funds to farmworkers. If not, here is an example of the coverage.

It’s hard to figure out where Florida Legal Services (FLS) could possibly be coming from with this lawsuit. But we do know this, it’s not coming from any basis in fact.

The lawsuit’s sole claim is that the money accumulated during the time when growers refused to participate, from 2007-2010, in the penny-per-pound program was never paid to workers. From the Ft. Myers News-Press:

|

“… But the money for the three harvest seasons was never paid, and no one will tell him where it is, said the plaintiffs’ attorney, Greg Schell of the Migrant Farmworker Justice Project… ‘The concern is, why has nobody paid this money, and we haven’t been able to get a good answer,’ Schell said. ‘The growers are willing to pay the money if somebody gives it to them.'” |

The Florida Legal Services attorney repeated his claim to the Naples Daily News:

|

“It wasn’t paid,” he said. “I promise you.” |

The problem with that claim is that it is dead wrong, and demonstrably wrong.

Easily verifiable

The money was paid to workers as a line item bonus this past season, the very first season after the growers agreed to participate in the penny-per-pound program last November.

Verite, the independent third-party monitoring the agreements this past season, can verify that. All the attorneys and accountants of the major fast-food companies that paid the money to the growers can verify that. All the attorneys and accountants of the tomato growers that passed the money on to the workers can verify that. And thousands of farmworkers who received the bonus payments can verify that.

And here, below, with your own eyes, you can verify it, too:

|

|

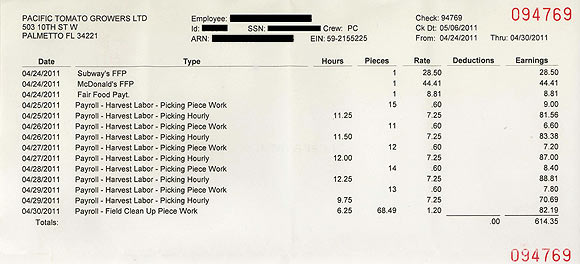

Above, a receipt from a Pacific worker from the last week of April of this year shows, in clearly labeled, separate line items, the bonuses paid from the Subway and McDonald’s accumulated, or “escrow”, funds (labeled “Subway’s FFP” and “McDonald’s FFP”) supplementing the regular penny-per-pound payment for current purchases, labeled “Fair Food Payt.” Any payments from Burger King’s accumulated funds would be included in the “Fair Food Payt.” line.

|

In short, the accumulated money was paid by the restaurant companies and distributed — to farmworkers, through the growers — just as intended and agreed upon. If that weren’t the case, we’d be the ones suing.

And, what’s more, Florida Legal Services was informed of this reality several months before it nonetheless decided to file the suit. Twice. From a letter to Mr. Schell, from the CIW’s attorney, dated May 9th, 2011:

|

“… As you know, during the current tomato season the FTGE and its members had a change of heart and agreed to participate in the CIW’s Fair Food Program. Implementation of the Fair Food Premium bonus system is part of the agreement with the FTGE and its members. As a result, Six L’s and Pacific again, and other tomato growers for the first time, have agreed to offer a bonus to qualifying workers. All of the money that has or would have been paid as a Fair Food Premium by participating purchasers since signing their agreements with the CIW (except for that from Yum Brands) is being paid to growers to fund the new bonus system. None of that money is being retained by any of the participating purchasers, including Yum Brands.” (emphasis added) |

And again, in a second letter, from June 2, 2011:

|

“… I am pleased that my last letter provided you with more insight into the operation of the Fair Food Program, but your most recent letter suggests that your understanding remains incomplete. Perhaps that is because you continue to operate from faulty factual premises, so I will try to address some of those in this response… … once the FTGE had its change of heart, those amounts [the penny-per-pound funds accumulated during the period the growers refused to participate], in addition to the amounts for current purchases, began to be paid out to current workers pursuant to a formula contained in the Fair Food agreements.” (emphasis added) |

During this same period, the CIW’s attorney wrote two more letters, this time to Kent Spuhler, Director of Florida Legal Services, to inquire if the attorney’s pursuit of these claims enjoyed the explicit support of FLS as an institution.

Mr. Spuhler never even afforded us the courtesy of a response. The reply came in the form of a press release announcing the filing of the lawsuit.

Sowing confusion

Our concern, however, is not with the lawsuit itself or its eventual outcome, but with the confusion it will create in the meantime.

This is a crucial moment in the Campaign for Fair Food. With nine multi-billion dollar retail food companies and the entire Florida tomato industry now on board, farmworkers in Florida are finally seeing the light of a new day dawning in the fields, with the beginnings of a better wage and a more modern work environment, including new protections, the right to complain without fear of retaliation, and a voice on the job.

It is still early in that new day, however, and the light is still dim. For the bonuses to grow, and the new protections to gain a strong and abiding foothold in the industry, more retail food companies, including the supermarket industry, must also do their part. But the fog of baseless claims contained in Florida Legal Services’ lawsuit could provide yet another excuse for those companies to continue their resistance to the Campaign for Fair Food.

And that would make the lawsuit as tragic as it is misguided.

Bonuses are not “back pay”

There is one more point that needs to be made.

Many of the articles that have come out about the lawsuit frame the story in terms of workers’ “back pay.” That is a misconception that is a perfect example of the kind of confusion a groundless and irresponsible lawsuit can cause.

The funds generated and passed on to workers through the Fair Food Program have always, from day one, been a bonus to supplement the workers’ pay, not the pay itself. As the CIW’s lawyer told Florida Legal Services well before they filed this suit:

|

“Indeed, it is very important to almost all the participating buyers that the additional money they agreed to pay for Florida tomatoes be treated as a Fair Food premium (akin to a fair trade premium) and not as salary…” (May 9th letter to Greg Schell) |

As evidence of this concern, when YUM Brands first started its payments back in 2005, it actually paid the bonus through a separate check to each worker. That cumbersome mechanism has now been replaced by a separate line item on each worker’s check (see above), but the bonus nature of the payments has never changed.

When the members of the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange decided in 2007 not to participate in the Fair Food Program, the fast-food companies agreed to calculate and set aside the amount of the price premium they would have paid if the Program had been operative. For YUM and McDonald’s, both of which signed agreements when FTGE members were still participating in the Fair Food Program, the decision to set aside the price premium amount was an entirely voluntary show of good faith, as their agreements could not foresee the growers’ eventual resistance and so did not contain any “escrow” provision. For the other companies, the agreements specified how to account for the money they would have paid if the growers were participating, and how to pay that money out, prospectively to workers then in the workforce, once the growers resumed participation.

Paying it forward

Why did we do it that way? Because it was by far the fairest and most efficient approach.

No one knew at the time of the agreements whether the growers’ refusal to participate would last 3 months, 3 years, or 30 years. Given the migrant nature of the work force, the astronomical turnover in the fields (it is estimated that a single picking “position” is occupied by at least 3 different individuals every 8-month season), and the amount of money that would inevitably be wasted attempting to locate long-gone workers (mostly without success), any effort at retroactive distribution would have made no sense at all.

And so, it was agreed that the accumulated money would be distributed, in the form of a bonus, to the workers in the industry at the time the growers ultimately relented, and that is exactly what was done. Together, the penny-per-pound based on current purchases (during the 2010-11 season) and the funds that had accumulated during the growers’ resistance, were paid to supplement the workers’ regular picking wages, giving the workers an additional bump until the accumulated funds were fully drawn down.

Looking back, given that the growers’ resistance lasted the better part of three years, the agreement to distribute the bonus prospectively was a wise one. By distributing the bonus funds to workers in the fields today, the agreed upon money has gone to workers in its entirety, through current payroll, at no additional cost and without delay.

On the other hand, if we had agreed that the accumulated funds would be paid backward, as Florida Legal Services seems to prefer, most of the workers would never be found (as they will have moved on to other employment or back to their home countries), much less get any money. Paralegals and lawyers, however, would get paid for doing the search for qualified workers, which could take years. This may make sense for lawyers and paralegals, but it doesn’t make any sense for the workers.

So, to summarize:

Paying it forward: Every penny of the money gets to the workers, at no additional cost, and with no delay.

Paying it backward: Only a small percentage (typically well less than half) of the money ever gets to the intended workers, and the search for workers is costly and time consuming.

Which approach would you choose if you had to decide? We think the choice is an easy one, which is why our agreements on the accumulated bonus funds from 2007-2010 require what they do.

Human rights, legal communities speak out on Florida Legal Services lawsuits

Human rights, legal communities speak out on Florida Legal Services lawsuits Ft. Myers News-Press editorial sets record straight…

Ft. Myers News-Press editorial sets record straight… But what’s not right is the irresponsible claim that workers are somehow being kept in the dark about the things in the agreements that pertain to their rights.

But what’s not right is the irresponsible claim that workers are somehow being kept in the dark about the things in the agreements that pertain to their rights.