[hupso_hide][hupso title=”Short title” url=”the URL”]

photos: Sarasota Magazine

photos: Sarasota Magazine

Beau McHan, Harvest Manager, Pacific Tomato Growers on the FFSC auditors: “They’re extremely thorough. Other auditors or inspectors might just poke their heads in, but these guys talk to pretty much every worker. Then they check their records with our office.”

In a must-read, well-written, wide-ranging article published in this month’s issue of Sarasota Magazine, entitled “Fairness in the Fields: A Sarasota Organization Brings Hope and Justice to Florida’s Tomato Fields,” freelance journalist Philippe Diederich takes a close look at the Fair Food Standards Council, the third party monitoring body for the Fair Food Program, and comes away impressed.

The article begins with a compelling depiction of the problems that had faced farmworkers in Florida’s tomato fields before the Fair Food Program:

Ten years ago, at the age of 22, Julia de la Cruz left her home and family in the mountains of Guerrero, one of Mexico’s poorest states. She hoped to make enough money working in the tomato fields of Southwest Florida to continue her studies and perhaps one day become a doctor. Instead she found herself trapped in a world of poverty and fear, where swaggering bosses bullied and abused the workers they employed.

“I’ve seen crew leaders keep workers’ paychecks. There was a lot of robbery,” she says. Some beat the workers and a few even held them captive. Women, especially, suffered at the hands of the leaders, who would harass them and sometimes demand sexual favors in exchange for giving them easier jobs.

“You see a lot of things you don’t like,” says de la Cruz, recalling working at a hothouse where she often had to put in 16-hour days seven days a week. At night, she’d fall asleep, exhausted, in a metal trailer filled with bunk beds holding other men and women.

The farm was in a remote area, miles away from the nearest small town. There was no way to leave. “And when you’re out in the middle of nowhere,” she says, “who would know if you were robbed or raped? Who would know?” read more

It goes on to tell the story of the Campaign for Fair Food and how the success of that campaign gave birth in 2010 to the Fair Food Program and the Fair Food Standards Council, interviewing harvesting supervisors from Pacific Tomato Growers, the first company to sign a Fair Food agreement with the CIW, for their impressions of the Program and the FFSC:

On a recent sunny morning, 31-year-old Beau McHan, a slim, easygoing, third-generation harvesting manager for Pacific Tomato Growers Ltd., stands in the sand at the end of rows of tomato plants that seem to go on forever in Field D8 of what he calls Farm No. 1 in Parrish in eastern Manatee County.

“Realistically,” McHan says in his slight Southern accent, “these changes should have been done years ago. The tomato harvest hasn’t changed since industrial tomato farming began in the ’40s and ’50s.”

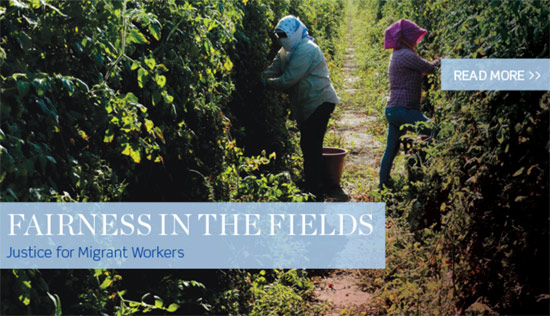

The harvesting, which is done completely by hand, is extremely labor-intensive. On this morning, migrant workers from Mexico and Guatemala are spread through the rows picking grape tomatoes. They wear long-sleeved shirts and gloves, and their heads and faces are covered in caps and bandanas to protect them from the sun and pesticides. Mexican Norteño music blares from a radio in the field as the workers silently pick the small tomatoes, dropping them into plastic buckets, which they carry to a flatbed truck. There another worker empties the tomatoes into a crate, drops a plastic ticket or token into the bucket and tosses the bucket back to the picker. The worker pockets the token, and at the end of the day crew leaders will tally the tokens and pay accordingly.

McHan explains that 10 years ago, Jon Esformes, operating partner of Pacific Growers, sat down with the members of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to find common ground. “There were no lawyers, no dramatics,” he says. In the end, he says, the changes were something both parties wanted.

Crew leader Manuel Villagomez, a portly man from Mexico’s Guanajuato state who wears a cowboy hat and smiles easily, showing off his two gold-capped teeth, says the changes he has seen in the 22 years he has worked for Pacific Growers have all been positive. “The people are treated better, the company pays for insurance for my bus. I have people that have eight or more years with me,” he says.

Villagomez started out as a picker. After a couple of years, he became a crew leader. As soon as the harvest is over, he will follow the season up to Georgia, Virginia and South Carolina before returning to Florida in the fall. And many of the Pacific Growers workers will follow.

Beau McHan attends to the FFSC auditors with ease and respect. “They’re extremely thorough,” he says. “Other auditors or inspectors might just poke their heads in, but these guys talk to pretty much every worker. Then they check their records with our office.” read more

The writer gives the last word to the CIW’s Julia de la Cruz, who captures both the remarkable changes that have taken place in the first few years of the Fair Food Program and the challenges still ahead with an admirable economy of words:

Julia de la Cruz has never realized her dream of studying or becoming a doctor in America. Instead, now a woman of 32, she picks tomatoes in Immokalee. “You earn very little,” she says.

But she’s quick to add that before the FFP things were much worse. She and other members of the CIW continue to canvas the fields handing out cards with the FFP’s 24-hotline and flyers for worker meetings at the CIW headquarters where they tell workers about their rights.

“I came to work and I’m going to work,” de la Cruz says as she prepares to leave Immokalee and follow the season up to Georgia and Virginia. “But now the fear is gone.”

The article is truly a must-read, providing a broad — yet remarkably deep — look at the history, mechanics, and future of the Fair Food Program. Click here to check it out!