Susan Marquis, Dean of RAND Graduate School, and author of “I Am Not a Tractor,” on the unique success and attention to detail of the Fair Food Program: “Getting things done is central to this story because to achieve the systemic change necessary to eliminate the causes of worker abuse, the program had to work; its success measured by metrics of real and enduring change in the fields…”

Today, we are delighted to announce the publication of the long-awaited 2017 Fair Food Program Annual Report! Hot off the presses after months of tireless work by the Fair Food Standards Council and CIW staff, the latest report provides the most recent results and analysis from Seasons 5 and 6. But unlike past reports, the 2017 version also tracks the trajectory of the Fair Food Program — the unfolding story of increasing compliance through the constant back and forth of audits, investigations, and corrections — over the course of all six seasons of the Program’s operation.

It is a thoroughgoing, transparent, and at all times honest look at the structure and function of the Fair Food Program, and how that structure has brought about a constant ebb and flow of change in Florida’s fields. Through carefully detailed quantitative and qualitative analysis, it tells the story of how that ebb and flow has, over time, fundamentally re-shaped an entire industry and, in the process, forged a model that is already bringing change to many more workers here in the US and overseas.

In this morning’s post, we bring you a brief overview of the different sections of the report. Today’s post will be followed by a closer look at the report’s core insights and conclusions later this week. So, if you do nothing else, do take a few minutes to read today’s post for a sense of the full scope of the 2017 report. But far better still, of course, is to read the report itself in its entirety, which you can find here. It is truly a must-read for all members of the Fair Food Nation, the surest way to know the full impact of the Program that we have all fought so hard to build and defend over these many years, and that has brought transformative and lasting change to the lives of tens of thousands of farmworkers from Florida to New Jersey.

Context and Introduction

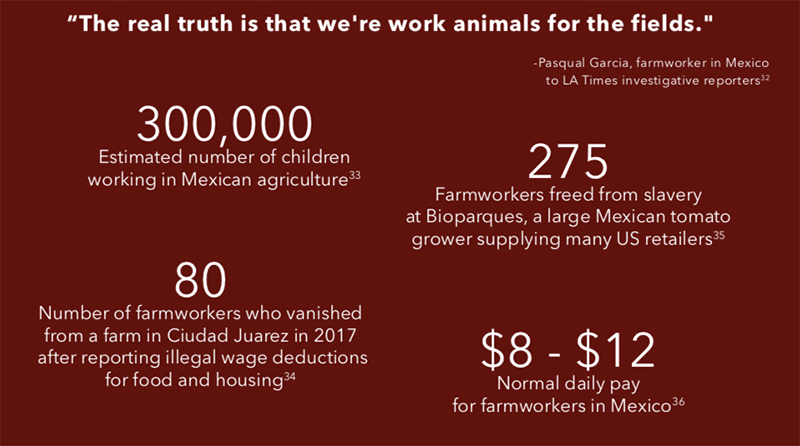

The 2017 Report begins by placing the Fair Food Program in its historical and industrial context, grounding the overall analysis of its gains in both the grim reality of the agricultural industry before the Fair Food Program, and in the abuses that persist today in fields beyond the reach of its protections:

Whether carried out by slaves, sharecroppers, or an immigrant labor force, farm labor has always been one of the lowest paid and least protected jobs in the United States.

Today, in both the US and many other countries, much of the food we eat is still grown and harvested by women and men who do backbreaking work for poverty wages.

When you walk down the produce aisle, what are you buying?

Was the human being who picked the produce treated fairly?

How can you be sure?

A new day dawns: The founding vision of the Fair Food Program

The report goes on to provide a concise reckoning of the dream of a more modern, more humane agricultural industry envisioned by the workers who have fought the many battles of the Campaign for Fair Food since 2001, a vision established in the Program’s Code of Conduct:

The Fair Food Code of Conduct was drafted by farmworkers who understood the harsh conditions in the fields, and who asked that they:

Not be the victims of forced labor, child labor, or violence.

Earn at least minimum wage.

Always be paid for the work they do.

Go to work without being sexually harassed or verbally abused.

Be able to report mistreatment or unsafe working conditions.

Report those abuses without the fear of losing their job – or worse.

Have shade, clean drinking water, and bathrooms in the fields.

Be allowed to use the bathroom and drink water while working.

Be able to rest to prevent exhaustion and heat stroke.

Be permitted to leave the fields when there is lightning, pesticide spraying, or other dangerous conditions.

Be transported to work in safe vehicles.

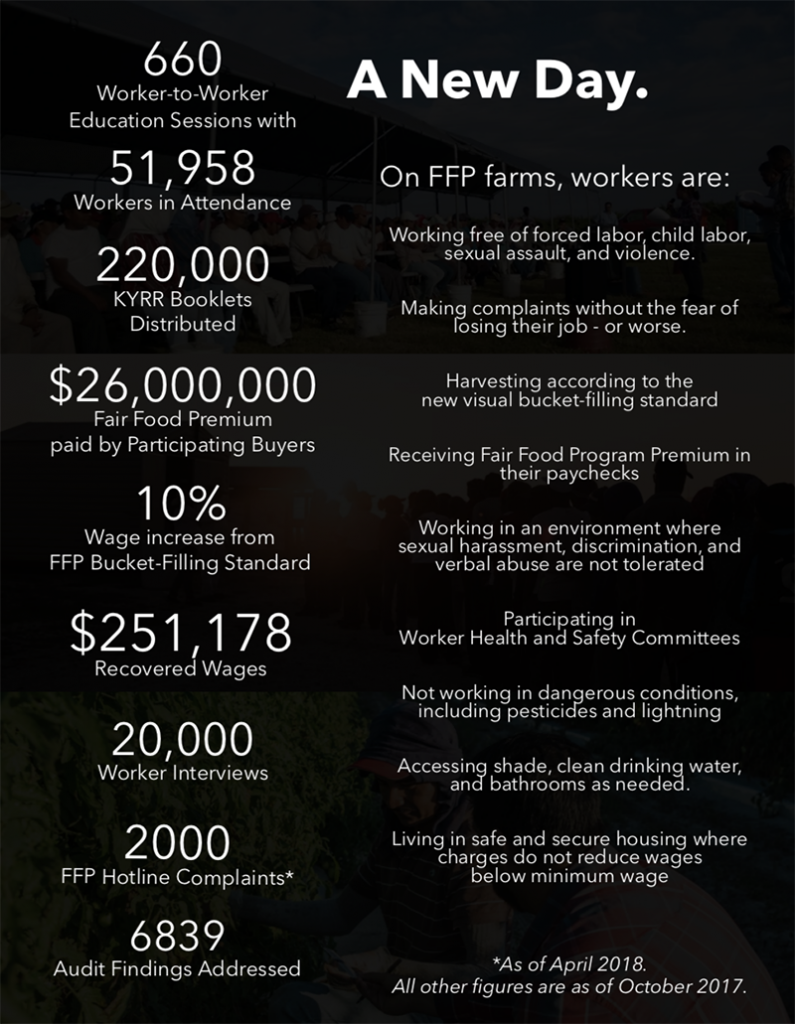

Following a description of the essential mechanisms of worker-driven, market-enforced social responsibility — worker-to-worker education, in-depth auditing, an efficient complaint resolution system, and market consequences — the report provides a full-page spread detailing to the Program’s impact as illustrated through numbers, figures generated by the Fair Food Standards Council’s meticulous documentation and recorded in the Program’s unique data base…

… followed by a summary of the staggeringly high praise it has garnered across the spectrum of human rights observers, from the Harvard Business Review and the New York Times to the White House and United Nations:

In Focus: Women in the Fields

Before launching into a detailed analysis of the Program’s results that makes up the body of the document, the 2017 Report takes a look at the experiences of three key groups of workers: Women in the fields (both outside of and within the FFP), farmworkers in the Mexican produce industry, and farmworkers in the U.S. beyond the protections of the Fair Food Program.

First, women in the fields, both within the FFP and beyond its critically-important protections:

If you’ve read the news lately, you already understand: sexual abuse at work is ubiquitous in the United States, but obstacles to reporting abuse make it difficult to quantify sexual harassment and sexual violence. Research suggests that at least 1 in 3 women experience sexual harassment in the work- place; however, an estimated 75% of workplace sexual harassment is never reported to employers or the government.

Sadly, women who do step forward are unlikely to achieve a successful outcome. In 2015, the EEOC investigated 6,822 allegations of sexual harassment in the workplace. Claimants were successful only 25% of the time, and these cases normally take years to resolve. Victims may want closure quickly. Witnesses may be reluctant to come forward. Beyond this, the legal system presents real challenges related to burden of proof and proof of injury.

For the hundreds of thousands of farmworker women in the US, the situation is much worse.

Human Rights Watch cites a 2010 survey of farmworker women in California’s Central Valley which found that 80 percent had experienced sexual harassment or assault. Indeed, sexual harassment and violence are so common that some farmworker women “see these abuses as an unavoidable condition of agricultural work.” As one female worker succinctly put it, “You allow it or they fire you.” […]

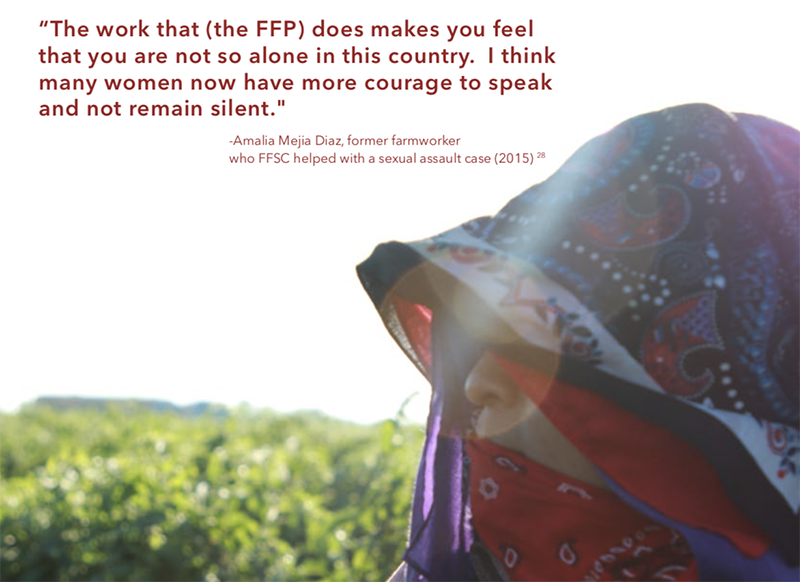

[…] Women employed at Fair Food Program farms now live a different reality.

With education on their rights effectively conveying the message that women no longer have to tolerate abuse, coupled with access to a protected complaint mechanism, farmworker women now speak up without fear of retaliation or inaction. Supervisors found by the FFSC to have engaged in sexual harassment with physical contact are immediately terminated and banned from employment at other FFP farms for up to two years. Participating Growers must carry out these terminations, or face suspension from the FFP with the accompanying loss of ability to sell to Participating Buyers. Supervisors terminated for less severe forms of harassment or discrimination also face a program-wide ban. Allegations of sexual harassment are investigated and resolved with unprecedented speed, averaging less than three weeks.

In Contrast: The Mexican Produce Industry

The second group of workers highlighted are those in the Mexican produce industry, which — during Florida’s growing season, between November and May — is the principal sourcing alternative for the country’s largest restaurant and supermarket chains:

The emergence of the Fair Food Program rapidly and significantly widened the human rights gap between the U.S. tomato industry and its competition in Mexico. At the same time that workers, growers, and retailers are making unprecedented investments to address poverty and human rights concerns in the U.S. tomato industry, the Mexican industry remains mired in gross and largely unchecked human rights abuses.

Due to the rapid growth of exports by lower-cost producers in Mexico, Florida growers have faced increasing price pressure. In Mexico, cost advantage is driven in large part by lower wages and inferior, often grossly abusive working conditions. […]

[…] In stark contrast to the situation in Mexican agriculture, Fair Food Program growers’ partnership with farmworkers and Participating Buyers has helped forge the most modern, humane workplace in global agriculture.

In Contrast: Outside the FFP, Inside the US

Finally, the report looks at the progress that remains to be made inside the U.S., where hundreds of thousands of farmworkers continue to work under perilous and degrading conditions:

The Fair Food Program has made tremendous progress since it was first implemented across the Florida tomato industry in 2011. However, much work remains to be done.

While key food industry leaders have joined the FFP, many more corporate buyers remain on the sidelines of what has become the most important farm labor reform movement in over a century for the East Coast’s agricultural industry. By refusing to join the Program, these non-participating buyers not only fail to shoulder their rightful share of the costs of safeguarding human rights in their supply chain but in fact undermine the progress that has already been made by exerting a destructive downward pressure on farmworker wages through their traditional volume purchasing practices. As importantly, non-participating buyers also continue to provide a “low bar” market for growers who are unwilling to meet the high standards and rigorous enforcement of the Fair Food Program. […]

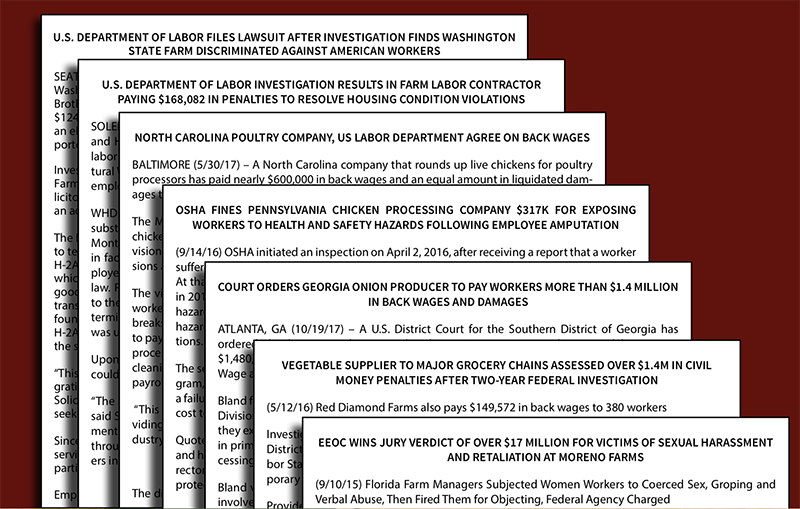

[…] Outside the protections of the Fair Food Program, U.S. farmworkers remain subject to a well-documented array of unfair labor practices and abuses that contribute to hostile and dangerous work environments. Even a small sample of news head- lines from recent years (see right) underscores the breadth and severity of these problems. In 2015, the EEOC won a jury verdict of more than $17 million in damages to female farmworkers who had been subjected to coerced sex, groping, and verbal abuse by farm managers while employed by Moreno Farms in Florida. Unfortunately, that judgment is unlikely to ever be collected from the company which ceased operations after the case was decided, leaving the owners free to reorganize and create similarly abusive environments for other workers.

In 2016, Red Diamond Farms, one of the largest Florida tomato suppliers that has refused to join the Fair Food Program, was assessed $1.4 million in penalties by the Department of Labor for unlawful hiring and pay practices. In 2017, Bland Farms – the largest grower of sweet onions in the United States – was ordered by a U.S. district court in Georgia to pay more than $1.4 million in back wages and damages to farmworkers. And a lawsuit filed in January 2018 alleges that operators of Saraband Farms, a Washington blueberry farm, repeatedly threatened immigrant workers with deportation, provided them with insufficient meals and told them to work “unless they were on their death bed.” Last summer, workers at Saraband Farm went on strike after one of their coworkers was hospitalized. Workers said that managers at the farm had ignored his requests to see a doctor before his death.

Unfortunately, until market-incentives are aligned so that it is more profitable to adhere to humane labor standards than to ignore them – until there is a credible, enforceable threat of losing market share as a result of unfair treatment of farmworkers – these headlines about remedies sought after abuses have taken place represent the best case scenario for many farmworkers.

The Road Ahead: Worker-driven Social Responsibility

That, however, is not the end of the story. Following the troubling reports of life outside of the Fair Food Program, the Annual Report documents the creation of the Worker-driven Social Responsibility Network, a group of diverse organizations set on bringing the remarkable changes wrought by the Fair Food Program to new industries and regions around the world:

The Fair Food Program, which is currently negotiating opportunities for expansion in two additional geographic regions and new crops, influences workplaces and supply chain initiatives far beyond itself. The FFP was the first comprehensive, fully functional model of the new Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR) paradigm, a human rights approach designed by workers themselves and anchored by legally binding agreements between the workers’ organization and the signatory retail brands who are the major customers of the suppliers who employ the workers. WSR holds tremendous promise for addressing human and labor rights abuses in global supply chains.

Internationally, WSR has been implemented through the 2013 Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh in that country’s garment sector. This followed a series of horrific factory fires and building collapses in the supply chains of major US and European clothing brands. Union and witness signatories to the Accord included two global labor unions, eight Bangladeshi labor federations, and four NGOs. With more than 200 brand signatories, the Accord covers some two million workers. Many of the factories that employ these workers have undergone a tremendous transformation to ensure their structural integrity and fire safety. In 2018, the Accord was extended five years to continue its progress. […]

[…] One of the [Worker-driven Social Responsibility] Network’s promising accomplishments on the ground is a nascent WSR adaptation on Vermont dairy farms known as Milk with Dignity. This program was created by Migrant Justice, a worker-based human rights organization, with multi-year technical assistance from CIW, FFSC, and other network members during four overlapping stages: exploration, standards development and program design; campaign and negotiations; and implementation. On October 3, 2017, Migrant Justice signed a legally binding agreement with Ben & Jerry’s to launch the program in that iconic brand’s supply chain. As of 2018, Milk with Dignity is now operational on Vermont dairy farms and monitored by the newly established Milk with Dignity Standards Council.

Results

In the central, deep-dive section of the report, readers get to dig into both concrete numbers and nuanced analysis of each of the Program’s core mechanisms, from Worker-to-Worker Education…

… to Auditing …

… to Market Consequences.

Following the mechanisms, the report provides a detailed look at the levels of compliance achieved for each of the rights under the Program, documenting the tireless back and forth of inspection and correction that has fundamentally transformed the working environment in Fair Food Program fields. This is the true meat of the 2017 report and its conclusions will be discussed in a second post later this week.

The 2017 report closes with voices of the workers themselves, collected in the process of thousands of audit and complaint interviews, a qualitative measure of the remarkable transformation on the ground:

While this post provides an overview of the Report, we once again encourage every single member of the Fair Food Nation to sit down with the Fair Food Program Report and read it cover to cover. The 2017 report, which covers two years in detail and tracks the broader trajectory of progress over the course of six seasons, is a comprehensive record of the profound progress we have been able to achieve together — as well as the challenges that the Program has faced along the way and the progress that remains to be made in the years ahead.

Please share the report far and wide with your networks, and keep an eye out for the second update on the 2017 annual report later this week!