And shareholders are looking for answers…

Venceremos founder Magaly Licolli: “Tyson must adopt worker-driven solutions—with a complaint process that is legally enforceable—to guarantee workers’ rights and dignity…”

As COVID-19 has laid bare, the millions of men and women that grow, harvest, and pack our food are essential to sustaining the nation. Yet, they have, for generations, been subjected to sub-standard housing and deplorable working conditions. As the CIW warned early in the pandemic, and the facts now painfully show, these conditions have meant that these workers have suffered tremendously, and disproportionately, from the pandemic. At least 86,908 meatpacking workers, food processing workers, and farmworkers have tested positive for COVID-19. Even more distressing, a recent study showed that food and agricultural workers have suffered the highest COVID-19 death rates of workers in any occupation. The full extent of the devastation is, sadly, still unknown.

Wendy’s – which for years has refused to join the Fair Food Program and its widely acclaimed, uniquely successful worker-driven model of social responsibility – has long been aware of the human rights risks in its food supply chain. In fact, in recent years, Wendy’s claims it has “expanded” its supplier code of conduct to respond to human rights “risk factors” from “the nature of agricultural work.”

These words ring hollow, however, in light of the many widely-publicized COVID-19 worker safety issues in Wendy’s food supply chain. Wendy’s beef supply was disrupted due to the spread of COVID-19 among its suppliers’ workers. Workers at Wendy’s supplier Cargill suffered the largest COVID-19 outbreak linked to a single facility in North America: 1,560 cases. Lack of protections at Tyson, another Wendy’s supplier, resulted in at least 12,275 workers contracting COVID-19 and the death of 39 workers. A wrongful death lawsuit alleges that Tyson managers laid bets on how many workers would get infected. Mastronardi Produce, a reported Wendy’s supplier, with a history of worker safety violations, owns Green Empire Farms, where more than half of the workforce tested positive for COVID-19. And while Wendy’s has said it did not purchase from Green Empire Farms directly, Wendy’s also fails to be transparent about which farms actually do comprise its produce suppliers.

As if to add insult to injury, Wendy’s honored Cargill and Tyson in its 2019 “Squarely Sustainable” supplier of the year award, just months before their plants were the site of major COVID-19 outbreaks.

Shareholders demand answers…

At Wendy’s supplier Tyson Foods, a shareholder proposal, presented at the annual shareholder meeting yesterday, criticizes Tyson for its lack of transparency on its human rights record. Meanwhile the chief of NYCERS — the largest city employee pension fund in the United States, managing hundreds of billions of dollars on behalf of over 350,000 people — has called for a securities investigation into Tyson, claiming that it misled investors regarding its handling of its workers’ safety. Additionally, earlier this year, Food and Water Watch, a food advocacy group, and Venceremos, a poultry workers’ rights organization that has highlighted worker deaths at Tyson, together filed a complaint with the Fair Trade Commission accusing Tyson of misleading consumers by stating it provides a “safe work environment.”

Magaly Licolli, a Venceremos founder and longtime CIW ally, presented the shareholder proposal at Tyson’s virtual shareholder meeting yesterday. Her statement of support highlighted the sharp difference between Tyson’s words and its actions:

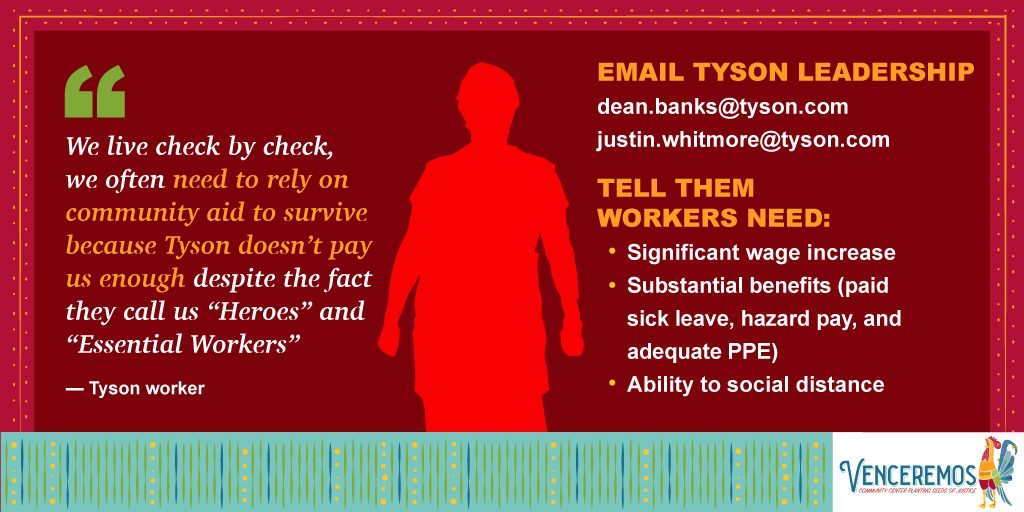

One would think that Tyson would provide workers, who Tyson once called “heroes”, with meaningful benefits and protections. Tyson workers have more than earned that support with their selfless sacrifice. However, Tyson has put profits before protecting workers’ lives. One worker stated to me, “Once we get injured, we are worthless to the company, they see us as expendable, not as human beings”.

Workers need, and deserve, a significant improvement in pay, paid sick leave, and safe working conditions. It is unacceptable that workers must rely on community aid to survive while working for the most powerful U.S. meat company.

Tyson must adopt worker-driven solutions—with a complaint process that is legally enforceable—to guarantee workers’ rights and dignity, and we urge all shareholders to support such solutions by voting yes on the resolution.

Meanwhile, in the world of Wendy’s shareholders, investors are also making the connection between the conditions in the food supply chain, and the responsibility of Wendy’s to protect those same food chain workers by joining programs like the FFP. Considering the stakes — namely, the very lives of essential workers that our country relies on to survive — the Wendy’s shareholder proposal is modest: a request for basic information on the measures Wendy’s has taken to ensure the human rights of workers in its meat and produce supply chains, and evidence those measures are actually working, including:

- Whether Wendy’s requires suppliers to implement COVID-19 safety measures;

- Whether Wendy’s has suspended suppliers for violating its code of conduct;

- How often Wendy’s audits suppliers for compliance; and

- Whether Wendy’s provides workers in its supply chain with access to an independent complaint system to report abuses.

Rather than provide this basic information, Wendy’s wants to omit the proposal from the materials it distributes to shareholders in connection with it’s 2021 annual shareholder meeting, and has asked for the SEC’s blessing to do so. (The SEC, or Securities Exchange Commission, is the federal agency that enforces securities laws, including whether shareholder proposals get to go forward or not.)

Wendy’s letter to the SEC unmasks the hamburger giant’s true feelings about what it owes to the workers it relies on for its product. Incredibly, Wendy’s directly states:

…we believe that the Company’s day-to-day operations of running a quick-service hamburger concept are far removed from any underlying policy consideration of the protection of human rights and worker safety of the country’s meat and produce Suppliers… the Company does not believe that the Proposal relates to a policy that is sufficiently significant to the Company such that it is appropriate for a shareholder vote.

In other words, Wendy’s response effectively denies the very concept of corporate social responsibility altogether.

While Wendy’s admissions are stark, its action in refusing to join the Fair Food Program speak even louder than those words.

The Fair Food Program stands alone among social certification programs in implementing mandatory, enforceable protocols to address farmworkers’ COVID-related health and safety concerns. Since the outset of the pandemic, the CIW and its FFP partners have worked tirelessly to secure community handwashing stations and crucial PPE for tens of thousands of farmworkers, significantly expanded testing sites in the farmworker community, advocated for vaccinations for essential workers in high-risk jobs, and, above all, drafted and enforced the FFP’s COVID-19 worker safety protocols on participating farms. Together, the CIW and FPP participating growers acknowledged, and acted on the fact that, for workers, these measures can mean the difference between life and death.

Despite these stakes, Wendy’s continues to shun the Fair Food Program and its uniquely successful worker-driven model of social responsibility, clinging instead to its in-house supplier code of conduct that contains no effective, accessible mechanisms to ensure protections for supply chain workers. And, in response to shareholders seeking evidence of how Wendy’s supplier code works in practice, Wendy’s has instead asked the SEC for permission to ignore that request and continue to keep its track record on human rights far away from public view.

Wendy’s loves to extol the virtues of its code of conduct and its corporate social responsibility program, which it calls “Good Done Right.” Wendy’s boasting – in light of its reluctance to share basic evidence of actual enforcement – only serves to further highlight the longstanding question: Is Wendy’s doing anything meaningful to protect the human rights of essential workers in its food supply chain?