Is hamburger giant’s move a genuine step toward real social responsibility, or just a ploy to relieve growing investor, consumer pressure to join the “gold standard” for human rights protections today, Fair Food Program?

Shareholders who filed the resolution seem skeptical, writing: “While this Board Recommendation to vote in favor of the proposal is welcome, investor support for the proposal… is warranted for the following three reasons:

-

Wendy’s has failed to demonstrate effective implementation of a meaningful commitment to respect the human rights of workers in its food supply chain and lacks transparency regarding its food supplier monitoring practices.

-

Wendy’s lags behind industry peers by failing to adopt the available measure most widely recognized as effective in preventing human rights risks in food supply chains and that addresses the concerns of the proposal, the Fair Food Program.

-

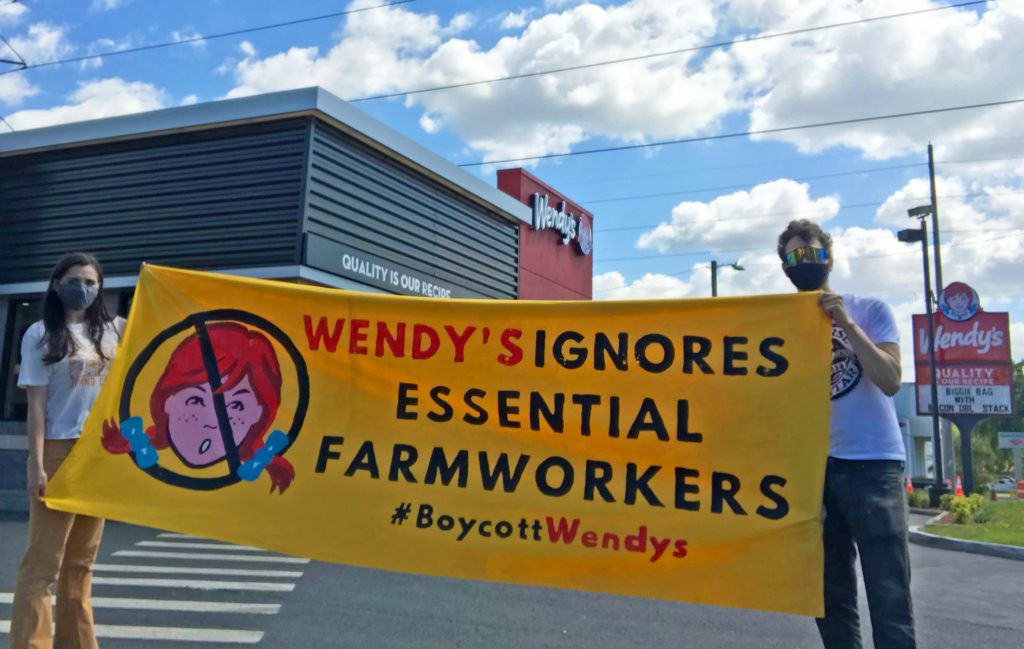

Failure to effectively address actual and potential human rights impacts in its food supply chain, including worker illness and deaths from COVID-19, exposes Wendy’s to financial, reputational, supply chain disruption and human capital management risks, and its failure to meet the industry standard for human rights protection, the Fair Food Program, has already resulted in potential reputational harm including consumer protests and public letters from key investors calling on Wendy’s to join.”

Wendy’s does a 180…

Well, we have to admit, we really didn’t see that coming. After all, when the Franciscan Sisters of Allegany first filed their shareholder resolution calling on Wendy’s to back up its claims of human rights compliance in its supply chain with real data, the hamburger giant did the predictable thing: It fought the resolution tooth and nail. Just three months ago, Wendy’s formally requested that the Securities and Exchange Commission allow the company to block a vote on the Sisters’ resolution at Wendy’s upcoming annual meeting, writing, for the record:

We believe that the Company’s day-to-day operations of running a quick-service hamburger concept are far removed from any underlying policy consideration of the protection of human rights and worker safety of the country’s meat and produce Suppliers.

Indeed, fighting the resolution for supply chain transparency was right on brand for Wendy’s, as was its unforgettably frank declaration that the human rights of workers in its suppliers’ operations are essentially none of Wendy’s business. But then Wendy’s lost before the SEC, and the resolution made it on to the ballot.

And so, with the battle lines drawn, the Sisters of Allegany, and the responsible investment organization Investor Advocates for Social Justice (IASJ) of which they are an affiliate, prepared for a campaign to educate their fellow Wendy’s shareholders on the justifications for their resolution in the weeks leading up to the annual shareholder meeting later this month.

Until Wendy’s decided to save them the bother and recommend, in its “definitive proxy statement” filed earlier this month, that its shareholders vote to support the resolution! And just like that, an otherwise straightforward “dog bites man” story takes a sudden turn, and observers watching what had been called “one of the 13 most important ESG resolutions” of 2021 in the pages of the Financial Times were left scratching their heads. Thankfully, the Sisters of Allegany and IASJ wasted no time in helping decipher the surprising news.

Trust, but verify…

So what’s really behind Wendy’s unorthodox move? Are we to understand that Wendy’s has seen the light and now sincerely believes, despite its unequivocal statement to the contrary just three months ago, that the fast-food brand does in fact bear some measure of responsibility for “human rights and worker safety” in its suppliers’ operations? What’s more, can we really expect to see some semblance of reporting that satisfies the resolution’s demands for disclosure? In short, can Wendy’s 180-degree pivot on the resolution be taken at face value, or should it be regarded with a heavy dose of skepticism?

One thing is clear, the Sisters of Allegany and IASJ aren’t buying Wendy’s change of heart. In their own filing with the SEC in response to the publication of Wendy’s proxy statement, they laid out the case for remaining vigilant and standing firm on their demands for real supply chain transparency and effective social responsibility. Their response is an impressive, thoroughgoing and well-reasoned analysis of Wendy’s track record on social responsibility and the threat that record poses for investors concerned about hidden reputational risks in Wendy’s supply chain. We recommend you read it in its entirety here, but for your convenience, here below are three extended excerpts that capture its argument. The response begins with a succinct summary:

Summary of the Proposal

The proposal asks for Wendy’s to disclose concrete evidence on the effectiveness of its Supplier Code of Conduct in protecting the human rights of workers at its produce and meat suppliers, with respect to COVID-19 in particular. Wendy’s is exposed to significant human rights risks in its food supply chain, which may have a material impact on the Company, yet existing disclosures do not reveal whether or how Wendy’s enforces its supplier expectations related to workers’ human rights. Wendy’s lags behind industry peers by failing to adopt the available measure most widely recognized as effective in preventing human rights risks in food supply chains, the Fair Food Program, despite requests from numerous investors. The requested report would include whether Wendy’s has implemented any requirements to protect at-risk farmworkers and meatpacking workers in its food supply chain from COVID-19, and the extent to which Wendy’s enforces its Code of Conduct to protect those workers through supplier suspensions, third-party audits, and access to remedy for human rights violations…

It then goes on to make a succinct case for shareholders to support the proposal, despite Wendy’s 11th hour about-face on its initial efforts to keep it off the ballot:

… Support for this proposal is warranted and in the best interest of shareholders because:

Wendy’s existing systems are inadequate. Wendy’s has acknowledged human rights “risk factors” in its food supply chain from “the nature of agricultural work,” risks that the global pandemic has heightened, particularly with respect to farmworkers who have disproportionately suffered sickness and death from COVID-19. Proponents are concerned that Wendy’s existing Supplier Code of Conduct lacks enforceable and binding commitments, and therefore is inadequate to address these risks. Moreover, Company disclosures do not demonstrate effective implementation of human rights protections for food supply chain workers, or give any indication that Wendy’s has standards and enforcement mechanisms in place requiring suppliers to protect these workers from COVID-19.

The risks in Wendy’s business model are severe and pervasive. In addition to the risks from COVID-19, other serious human rights violations are prevalent in the U.S. agricultural industry, such as forced labor and sexual assault. Wendy’s must be transparent about whether (and, if so, how) it enforces its supplier expectations to identify, mitigate, and prevent these risks and remedy negative impacts.

Although Wendy’s unsuccessfully sought No Action relief from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) if it omitted the proposal, the Company now recommends that shareholders vote FOR the proposal (“Board Recommendation”). While this Board Recommendation to vote in favor of the proposal is welcome, investor support for the proposal will reinforce the Proposal’s call for Wendy’s to disclose the concrete evidence of implementation, as only this evidence will sufficiently reveal how Wendy’s is managing human rights risks. Shareholder support will also clarify that Wendy’s current ESG reporting, which its Board Recommendation represents as a practice it plans to continue, is unacceptable because it does not contain the evidence requested in the proposal…

At the heart of the response is a point-by-point breakdown of the inadequacies of Wendy’s current social responsibility efforts when compared to the proven, best-in-class monitoring and enforcement mechanisms of the Fair Food Program:

… The Board Recommendation points to Wendy’s existing policies, procedures, and disclosures in an effort to demonstrate its commitment to the protection of workers in its supply chain. However, those materials are not responsive to the disclosure requested by the proposal, which seeks evidence of the effectiveness of Wendy’s existing Code and whether Wendy’s actually enforces its supplier expectations. For example:

- Wendy’s claims that violations of its Supplier Code of Conduct may result in “immediate termination.” However, Wendy’s code provisions on supplier labor practices and human rights are mere “expectations,” and, more importantly, Wendy’s has provided no evidence that they are enforced as sought by the proposal. In contrast, the Fair Food Program requires that its Participating Buyers (such as McDonalds and Burger King) suspend purchases from participating farms that are suspended from the Program. For example, if forced labor is discovered on a participating farm, or if a participating farm refuses to terminate a supervisor found to have sexually assaulted a farmworker, that farm is suspended from the Fair Food Program, and the Participating Buyer in turns suspends its purchases from that farm.

- Wendy’s refers to Quality Assurance audits containing “observational questions” related to worker safety and health, and to conducting its own remote “facility evaluations” during COVID-19, but these are directed primarily at food safety, not worker welfare, and are incapable of detecting hidden abuses such as forced labor, sexual assault, debt bondage or wage theft, which are recognized as salient risks in agriculture.

- While Wendy’s refers to “third-party assurances” and “audits” related to supplier labor practices and human rights, it does not disclose information sought by the proposal, which would indicate whether these audits are effective at addressing and mitigating human rights risks that may negatively impact the business and shareholder value. This includes audit frequency or the percent of workers interviewed, which relate to whether those audits have any informational value. In the Fair Food Program, the Program’s third-party auditor, the Fair the Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC), audits every participating grower annually and regularly publishes detailed information on farm compliance. Audits include in-depth interviews with at least 50% of workers present at each farm location visited – many times higher than the auditing industry standard – and auditors are ensured access to farm and office records and supervisory staff.

- Moreover, audits alone are not effective to identify and respond to the Company’s most salient human rights risks, and Wendy’s has not disclosed any evidence that those audits are supplemented by other essential mitigation measures, such as actual enforcement or an effective third-party complaint resolution system. In the Fair Food Program, the FFSC provides a worker complaint hotline, staffed 24/7 by investigators who speak the workers’ language, and between November 2011 and October 2018, 52% of complaints were resolved in less than two weeks and 79% in less than a month.

- Wendy’s claims to have a “robust reporting process” designed to protect workers in its supply chain, and refers to its company-sponsored hotline, but investors are concerned about whether this is true in practice because its No-Action Request to the SEC stated that “in most instances, it would not be appropriate” for Wendy’s to be involved in those complaints and that they are referred directly to the supplier — the very party against whom the complaint of abuse has been lodged. Additionally, Wendy’s does not disclose the number of grievances reported to its hotline, nor how they were resolved, which is information sought by the proposal that would provide some indication of whether Wendy’s complaint process is as robust as it claims.

- Wendy’s also suggests that the workers in its food supply chain are amply protected by “any COVID-19 orders and mandates issued” in relevant jurisdictions and “a wide array of employment and labor laws and regulations.” These statements ignore that most U.S. jurisdictions still lack enforceable COVID-19 protocols for farmworkers, and that legal violations are the norm—not the exception—in American agriculture due to numerous barriers to access to justice, including poverty, migration, education level, immigration status, and language differences. In contrast, the Fair Food Program enforces mandatory COVID-19 safety protocols for farmworkers on all participating farms…

The world has changed… Can Wendy’s?

The essence of the shareholders’ response is perhaps best captured in these two sentences:

… It is no longer sufficient to simply “check the box” when it comes to protecting workers from human rights violations in corporate supply chains. In the midst of both an unprecedented global pandemic and a global movement demanding racial and economic justice, consumers and investors alike are looking to corporations, and the executives and board members who lead them, to address longstanding social ills and to embrace efforts, like the Fair Food Program, able to demonstrate measurable success in curing them.

In short, with their response, the Sisters of Allegany and IASJ want to remind their fellow shareholders — and most of all Wendy’s itself — of the true meaning of their resolution: The time for empty, performative corporate social responsibility programs is over. The time has come for real change, change driven by workers and communities themselves and supported by the corporations that have profited from their poverty and exploitation for too long, change that can be seen, felt, and measured.

These past many months have surfaced the many longstanding inequities at the heart of the food industry for all to see, and in so doing they have also exhausted the patience of consumers and investors alike with the superficial, ineffective approaches to supply chain management that have been the dominant paradigm for corporate social responsibility for decades. And, for the authors of the shareholder resolution coming up for a vote on the 18th of this month, it would seem that the same goes for Wendy’s decision to embrace their resolution, too.

With its surprising about-face, Wendy’s may have simply realized that it was destined to lose the vote anyway, so better to get ahead of it and embrace the inevitable outcome. Or, the company may have hoped that by supporting the resolution it could take the wind out of the sails of a responsible investor movement that was gaining momentum by the day. But the shareholders’ response to the unexpected turn of events makes one thing abundantly clear — Wendy’s recommendation in favor of the resolution has done nothing to dampen the shareholders’ support for real, measurable social responsibility, and for the flagship program in that growing movement, the Fair Food Program.

What happens next is still to be seen. The meeting is on the 18th of this month, and the result of the vote will be released then. But even if the resolution wins the day, ensuring that Wendy’s actually satisfies the disclosure called for will almost certainly be a campaign all of its own. Victory in the world of shareholder action is rarely definitive. But the battle at Wendy’s upcoming shareholder meeting is just one front in a much larger struggle over the role of corporations in protecting human rights in their supply chains in the 21st century — a war between the expansion of Worker-driven Social Responsibility and business as usual, between substance and illusion — that is playing out across global supply chains today. Check back soon for a reflection on that broader conflict, and for all the news from the Campaign for Fair Food and the Fair Food Program.