Today we are thrilled to preview the 2021 Fair Food Program “State of the Program Report!”

QUICK LINK: 2021 Fair Food Program Report

Ten years in, one of many factors that continue to elevate the Fair Food Program over less rigorous “social auditing” and PR-driven corporate social responsibility schemes is the Program’s level of data collection, analysis, and transparency of results. The Fair Food Standards Council, the third-party monitor that oversees enforcement of the Program’s standards, produces the report for each season by interpreting all the quantitative and qualitative data that FFSC investigators and analysts collect from audits, hotline calls, education sessions, corrective action plans, and worker interviews. That data is enhanced by “in focus” essays that contextualize the Fair Food Program’s results in the larger landscape of agriculture and the many challenges — from Covid to climate change — of an ever-changing world.

Today, we’ll take a dive into some of the key findings of the report, which covers Seasons 8 and 9 (2018-2019, 2019-2020), plus some important highlights from 2021. But before we do that, we’ll share some updated cumulative data points from the Fair Food Program to set the stage:

Part One: “In Focus” essays encapsulate the resilience and innovation at the heart of the Fair Food Program

COVID-19

Members of the Fair Food Nation already know that the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly dangerous for farmworkers, and has forced millions of essential workers to make the impossible choice between personal safety or economic survival, with most having no real choice but to go to work and expose themselves to a deadly virus. Newspaper headlines from New Jersey to California lamented the extreme danger that farmworkers have faced — without pause — since spring of last year, as the mass outbreaks foreshadowed in the CIW’s New York Times op-ed came true.

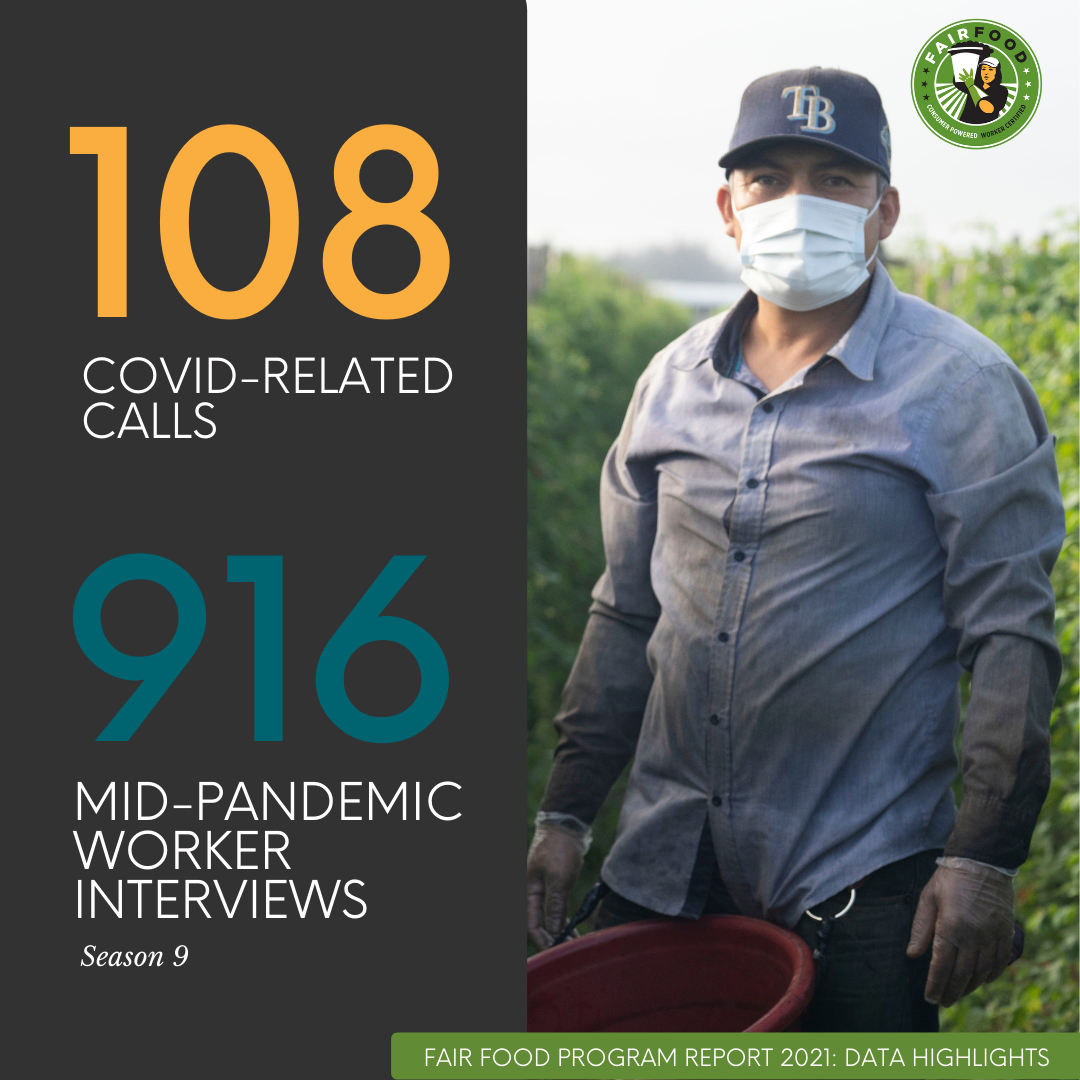

With that grim reality as the backdrop of Season 9, the CIW and its grower partners in the Fair Food Program did something extraordinary: they created the first and only mandatory, enforceable COVID-19 protections in agriculture. Those protections are detailed in the report, along with a look at how the Fair Food Program adapted to the pandemic over the past 18 months. While the CIW leveraged its time-tested tools of community outreach, education, and organizing to inform and protect workers and their families in Immokalee, the FFSC pivoted, too – creating new protocols for conducting interviews and audits, upgrading technology, and ensuring that the Fair Food Program could serve as not just a hotline, but a lifeline for workers.

Heat Stress Illnesses

Unfortunately, coronavirus is not the only danger stalking our country’s essential workers. Brutal summer temperatures, the undeniable measure of the growing threat of climate change, dominated the national headlines this past summer as outdoor workers, from construction sites to the fields, suffered widespread heat-related illness. Work that is already physically challenging now has the potential to become unacceptably dangerous, and even deadly.

In the absence of federal protections, the CIW, FFSC, and Participating Growers once again came together and rose to the challenge to address this latest threat. Echoing the collaborative problem-solving approach taken to create the COVID-19 protocols, the FFP Working Group researched, debated, and drafted a comprehensive policy, effective immediately, that requires mandatory breaks, sets forth action steps to prevent and respond to signs of heat-related illness, and complements existing Fair Food Program protections around shade and water.

Expansion

An unexpected bright spot in a dark year, the expansion of the Fair Food Program into new states and new crops continued apace despite strong pandemic headwinds, a testament to the Program’s powerful appeal and potential. Expansion driven by both Participating Buyers and Participating Growers has taken us into new territory with a huge tomato operation in Tennessee, fresh-cut flowers in Virginia and California, and sweet potatoes in North Carolina, with many more farms on the horizon. Alongside this traditional expansion pathway, the Fair Food Sponsor Program has emerged since the last report as a new way to connect to the Fair Food Program, as local co-ops and independent grocers put their values into practice by directly supporting the FFP and educating their customers about the Program.

Part Two: 2021 Report Results Highlights

This year, the “Charting Progress” report has been updated to include overall grower compliance scores for Seasons 8 and 9. The average compliance scores give us a snapshot of how well Participating Growers are complying with each of the protections in the Program. The scores have continued to climb, and this past season reached their apex at 95.

Key takeaways from this year’s State of the Program Report:

- The vast majority of complaints are able to be addressed and resolved, and the share that are resolved even when a code violation is not determined continues to be substantial. As we have noted in previous reports, this latter result is an indicator of the degree of cooperation on the part of Participating Growers to resolve worker complaints, as these are issues that don’t require action on the part of growers.

- Related, this year we continue to see a steady rise in the number of complaints originating through the Grower, wherein the worker has initiated a complaint through the Grower’s HR process first. This could be another indicator of not only cooperation but of growing faith on the part of workers that taking their complaints to their employers is a safe and efficient way to register complaints with the FFSC. Of course, the chart still shows that the FFSC and CIW pathways are critical, but this is nonetheless a positive indicator.

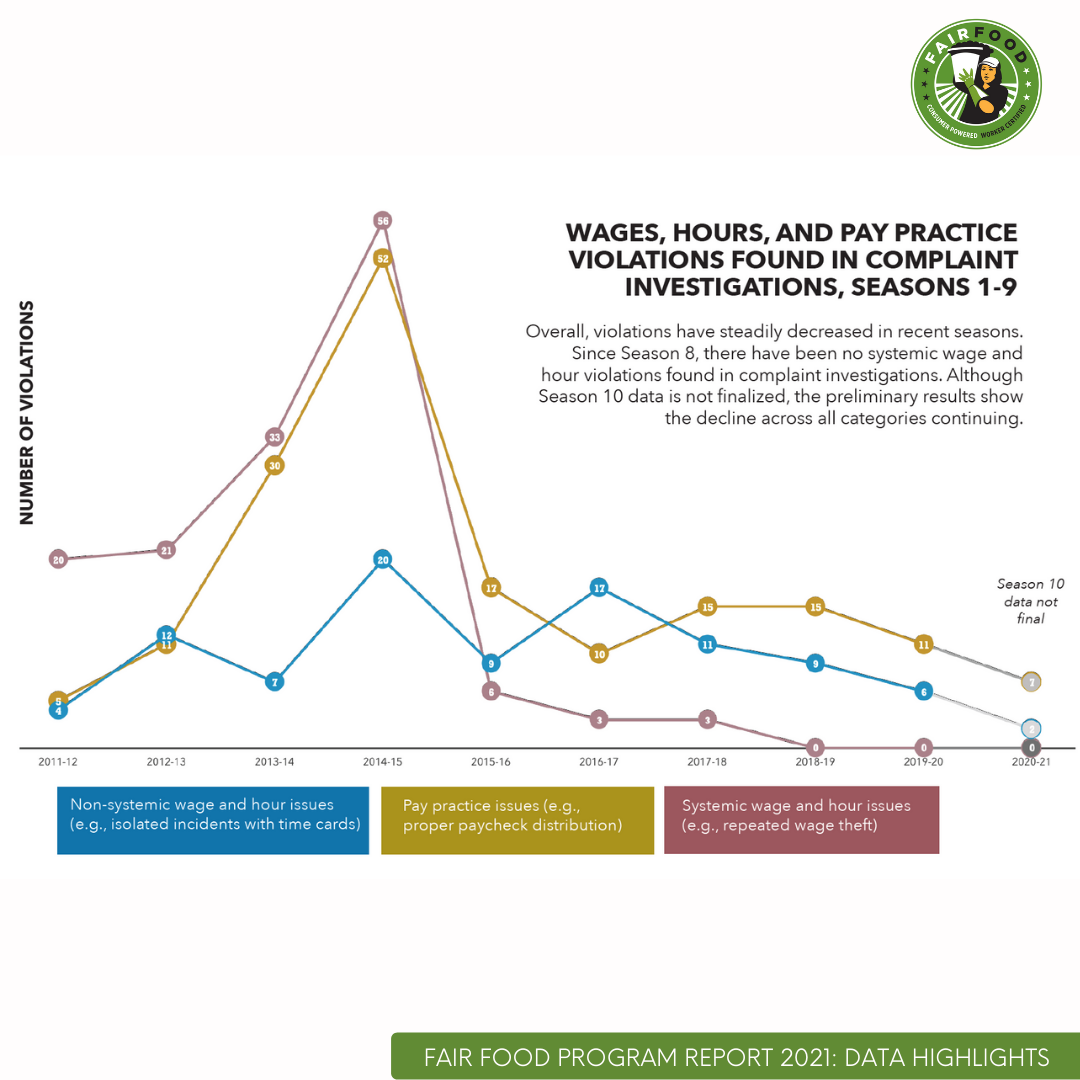

- Other positive trends are the steady reduction in reports of retaliation violations and wage and hour violations. These downward trends are consistent with the rise in average compliance scores. Importantly, the number of Article 3 violations (which are less grave than Article 1 and 2 violations) is not zero. The reality is that any accurate monitoring of labor conditions in agriculture in the United States will inevitably find some issues requiring corrective action. And in fact, that’s the point of the Corrective Action Plan, or “CAP,” system: it’s never a question of punishment and perfection, but of partnership and progress. Thus, the indicators the FFSC looks for are: are the violations becoming less severe? And, when there is a violation, is it addressed and remedied quickly and effectively so that it is less likely to happen again? For these questions, we can see the answer is yes when it comes to retaliation, wage and hour issues, and sexual harassment.

Building for the Next Ten Years

It’s worth remembering what makes the Fair Food Program so effective. It’s not the sharp analysts, thorough investigators, or dynamic worker education team alone. It’s not even the worker-driven Code of Conduct or 24/7 trilingual hotline. What makes the Program work, earning it the reputation as the new “gold standard” for human rights in corporate supply chains, has everything to do with what lies beneath the day-to-day operations: real enforcement.

When farmworkers with the CIW made the decision to focus their attention at the top of the supply chain, zeroing in on the source of the downward pressure on wages and working conditions that they were feeling daily in the fields, they tapped into a truth that has borne out year after year in the Program: real market consequences are required to guarantee real change. Lofty talking points, fancy websites and brochures, and “stakeholder engagement” that happens around conference room tables in most corporate-driven certification programs are simply no match for the harsh realities of business on the ground. By tying compliance to sales, the Fair Food Program made the choice to protect human rights into a smart business decision. Along the way, Participating Buyers and Growers in the Program have seen that this decision to affirmatively protect human rights benefits them, too: Retailers can actually back up their claims of social responsibility with their shareholders and customers, while growers can reduce their risks, strengthen their internal systems, and become workplaces of choice with less turnover.

The lessons of the first ten years of the Fair Food Program, the pioneering example of the Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR) model, continue to be collected and applied to new industries, and the concluding section of the report catches readers up to the newest WSR adaptations in progress, including an exciting new initiative in the construction industry in Minnesota and our recent consulting partnership with the Hollywood Commission to address sexual harassment, discrimination, and abusive workplaces in the entertainment industry.

We encourage you to read through the full report, which gives a complete breakdown of the data for each of the areas of the Fair Food Code of Conduct. Check out the report here!