Doug Molloy, former US Assistant Attorney: “It is my belief that they were killed because of their color.”

“Lucas Benitez, a founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, likened police officers in Immokalee to the US Army occupying Iraq.”

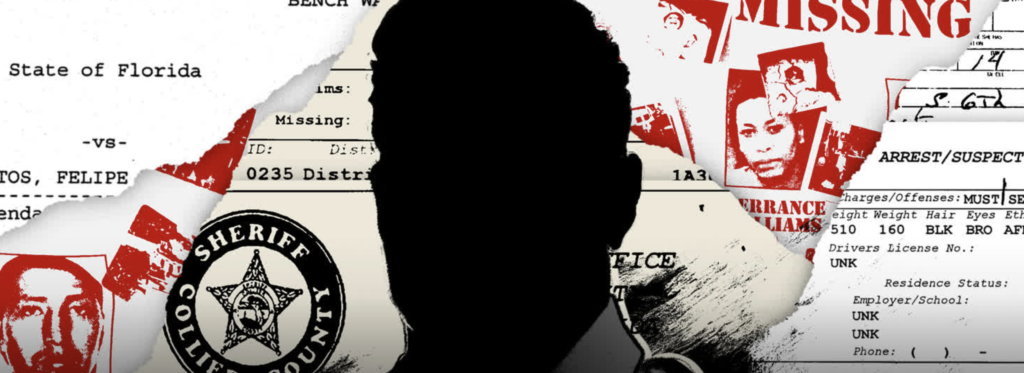

Around twenty years ago, two beloved sons and fathers — Felipe Santos and Terrance Williams — went missing in Southwest Florida. One, Felipe Santos, was part of the CIW family, brother-in-law to former CIW staff member Francisca Cortez. Both were last seen alive in the back of former Collier County Sheriff’s Deputy Steve Calkins’ police vehicle.

The story of Felipe Santos and Terrance Williams’ disappearances is one of tragedy and unresolved loss, but it is also a story about powerlessness – the powerlessness of two poor communities, Black and Latino, in wealthy Collier County; the powerlessness of disenfranchised residents in relation to a county Sheriff’s department with a long record of misconduct; and most of all, the powerlessness of two grieving and bewildered families seeking answers but left only with more questions, and still without their loved ones, two decades later.

But now, twenty years since the disappearance of Felipe Santos and Terrance Williams — one after the other, three months apart — CNN has published an in-depth investigative report detailing Williams’ and Santos’ lives and their last known minutes with Officer Calkins, whom many suspect to be behind their disappearances. NPR has also conducted a thorough investigation into their disappearances in a serialized podcast called The Last Ride, which is helping to focus national attention on this ongoing tragedy. Both are can’t-miss reporting.

CNN’s investigators interviewed nearly 70 people, including CIW staff member Julia Perkins and CIW co-founder Lucas Benitez, who both knew Felipe Santos and his family. In their account of Santos’ disappearance, Perkins and Benitez offer a vivid and unflinching look into the struggle for Immokalee’s working community to gain the kind of power needed to be treated as full human beings, and of the community’s historically fraught relationship to Collier County law enforcement.

The families of Terrance Williams and Felipe Santos deserve justice and closure to this 20-year crime, and while we may be still tragically far from the day that justice may be done, these stories are an important step in that direction.

The CNN investigation is long, but well worth the read. Below is an extended excerpt from the piece.

The deputy and the disappeared

A Latino man and a Black man went missing three months apart in Florida. Both vanished after getting in a patrol car driven by the same White deputy sheriff

By Thomas Lake, April 21, 2023

Naples, Florida — One morning 19 years ago, Marcia Williams woke up praying for her son. Terrance worked two jobs, and liked reading about Socrates, and had a scar on his right hand, near the thumb, from one time when he played with matches as a little boy. He was Marcia’s only child. She prayed and prayed, fighting against this inexplicable feeling that something terrible was about to happen.

A few hours later, Terrance crossed paths with a deputy sheriff. He got in the deputy’s patrol car. Then he disappeared.

The deputy said he’d given Terrance a ride to a Circle K convenience store. But there was no proof that Terrance arrived at the Circle K. And his mother never saw him again.

Eventually, Marcia learned something astonishing about this deputy sheriff.

Three months earlier, another man had also taken a ride in his patrol car.

Just like Terrance Williams, Felipe Santos had been driving illegally.

Just like Williams, he encountered Cpl. Steven Calkins of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office.

And just like Williams, he disappeared right after that.

The deputy said he’d dropped Santos off at a Circle K convenience store. But there was no proof that Santos arrived at the Circle K. And his family never saw him again.

Calkins is White. Santos was Latino. Williams was Black.

“It is my belief that they were killed because of their color,” said Doug Molloy, who was an assistant US attorney in 2004 and led a multi-agency task force that investigated the disappearances as potential hate crimes.

Sheriff’s investigators surveyed the evidence and determined that Calkins was not telling the truth about his encounter with Terrance Williams. One investigator made a list of nearly two dozen untruthful or inconsistent statements that Calkins made about the day he met Williams. In August 2004, about seven months after Williams disappeared, then-Sheriff Don Hunter fired Calkins. As he later wrote, “I have lost trust in Calkins and his ability to describe incidents in detail and to recall them.”

Meanwhile, investigators got to work. They searched the woods and the waters near where the missing men were last seen. They put a tracking device on Calkins’ car. They did a complete forensic inspection of the car, paying special attention to the trunk. No trace of Santos or Williams turned up.

The FBI delivered a target letter to Calkins and asked him to answer questions from a federal grand jury about the disappearances. Calkins declined. And the investigators’ suspicions did not lead to probable cause. No one could prove these were hate crimes, or even crimes at all. Years passed, and the cases remained open, and both men’s children grew up without their fathers. Calkins repeatedly denied harming the men. He was never criminally charged.

Now 68 years old, Calkins was last known to be living in Iowa. Through his attorney, he declined multiple interview requests from CNN.

Marcia Williams kept a lock of her son’s hair, and a picture of him, wearing a navy blue T-shirt, looking at the camera, which made it seem as if Terrance were looking at her when she walked past. And across the Gulf of Mexico, in the state of Oaxaca, friends and relatives remembered Felipe Santos.

“He didn’t deserve to be disappeared in this way,” his friend Francisca Cortés told CNN. “It isn’t right that he hasn’t been found after so many years and we don’t know what happened to him. As his parents say, ‘If we find his remains, we can give him a Christian burial so we have somewhere to cry and pray for him.’ But in this case there isn’t anywhere. And there isn’t any way to do that. Everything is in limbo and we are never going to know what happened.”

…

Lucas Benitez, a founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, likened police officers in Immokalee to the US Army occupying Iraq.

“It doesn’t know its traditions, its culture,” he said. “They are basically planted there. The Army goes to a small town in Iraq, doesn’t speak the language. The Army automatically feels attacked. What does it do? Aim its rifles. Immokalee was like this.”

…

Nevertheless, about six months after Williams disappeared, Sheriff Don Hunter circulated a “position statement” about the “apparent disappearances” of Santos and Williams. It alluded to legal trouble both men had. Santos was an undocumented immigrant who would have to answer for driving without a license. Williams faced no local charges, because Calkins hadn’t arrested or ticketed him, but a judge in Tennessee had issued a warrant for Williams in connection with unpaid child support.

“These men may therefore be purposely avoiding being found by law enforcement,” the sheriff’s statement said.

Julia Perkins, who knew Santos through the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, did not like what the sheriff was implying.

“That just seemed like an excuse,” she said. “And honestly, it was a slap in the face to the families.” Like others who knew Santos, she found it implausible that he would have willingly left behind his common-law wife and their three-month-old daughter. A picture showed him cradling the baby in his arms.

“He was not a person who was going to abandon her,” Lucas Benitez said. “He loved Apolonia and he was very happy about his girl’s arrival. They didn’t have any problems between them. They were two young people starting a life. They had dreams and plans together.”

In addition to CNN’s story, NPR’s podcast The Last Ride features audio recordings of countless people who either knew Felipe Santos or Terrance Williams, or were involved in the subsequent investigations. Conducted by a joint-team of reporters with WGCU, Naples Daily News, and Fort Myers News Press, the podcast explores the immediate circumstances of their disappearances, as well as the racial biases that likely contributed to both their untimely deaths and the disappointing lack of national concern after they disappeared. You can listen to the podcast on every major audio platform, or by clicking here.