AMAZING (DIS)GRACE…

Burger King, tomato growers’ strategy exposed: Industry giants team up to sabotage progress for farmworkers.

Strategy may backfire as public reaction summed up in words of recent op/ed: “OK, consumers, sic ‘em.”

As the 2007 March on Burger King rapidly approaches, a flurry of articles on the Campaign for Fair Food has hit papers across the country. The recent surge in coverage was sparked by the revelation that Burger King has joined forces with the most conservative elements of the Florida tomato industry to launch an aggressive assault on the CIW’s groundbreaking agreements with fast-food leaders Yum Brands and McDonald’s.

Four recent articles cover the story from several different angles:

- “At a penny per pound, a little adds up to a lot,” St. Petersburg Times, 11/24/07

- “Today’s bounty didn’t pick itself,” Palm Beach Post, 11/22/07

- “Tomato deal threatened by Burger King, growers,” Associated Press, 11/23/07

- “Tomato growers: We’re not bad guys,” Miami Herald, 11/19/07

The assault is apparently spearheaded by some back-room, strong-arm tactics by the state’s tomato lobby, which has been caught threatening to slap any grower who tries to sell tomatoes to Taco Bell or McDonald’s under the terms of the agreements with a fine of at least $100,000. The revelation has brought some unwanted attention to the secretive lobby, however, as lobby spokesperson Reggie Brown refused to answer questions about the fine, responding only that the exchange is “a private business enterprise that is not subject to public scrutiny.”

Fasten your seatbelts, it’s fixing to get bumpy…

BK, growers’ strategy revealed in two recent articles

Two articles from the past week — “Tomato growers: We’re not bad guys,” in the Miami Herald and “Tomato deal threatened by Burger King, growers,” by the Associated Press – revealed telling details of the two-pronged strategy launched by this new partnership of fast-food and tomato industry representatives. The strategy combines two key elements:

- A high-profile public relations campaign designed to sell an idea that turns common sense on its head: Farmworkers are not only not poor, but in fact many earn better wages than the majority of Floridians.

- Behind the scenes pressure on growers who have participated with Yum Brands in the Taco Bell agreement over the past two seasons to force them to end their sales to Taco Bell – and head off any sales to McDonald’s – under the terms of the agreements.

|

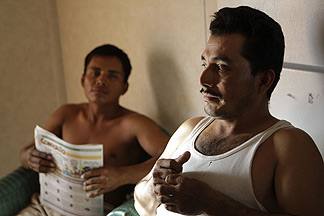

| From the Miami Herald report: “Wilbur Estrada Sanchez and Ezekiel Martinez bemoan the fact that they are working few hours as they relax in their trailer during a tour of a migrant labor camp organized by Burger King and area growers.” Photo by Nuri Valbona, Miami Herald staff |

The Miami Herald article reflected the almost desperate tone to Burger King’s public relations partnership with the growers. The article was the product of a trip to the fields of Immokalee organized for the Herald’s benefit by a team of BK public relations executives. With a willing reporter in tow, it seemed like a great idea, except reality just wouldn’t cooperate.

First, the workers interviewed could hardly be described as “satisfied.” Instead, they complained, “we’re not making ends meet” (sounds familiar….) and pointed to their irregular hours as the reason they were unable to earn a decent income.

Second, the delegation included a visit to a local charity, the Redlands Christian Migrant Association, where Burger King displayed its largesse by donating $25,000 to the group that, according to the article, “provides child care and education for migrant and low-income families.” Hmmm… Low-income families… Charities for low-income workers who are, according to the central premise of the public relations campaign, not poor. The contradiction couldn’t be missed.

So an article intended to lay to rest the idea of farmworker poverty ends up interviewing poor workers dissatisfied with their income and covering a visit to a charity for poor workers whose children qualify for low-income services. How did it go so wrong?

The central premise of the PR campaign is the Florida Tomato Growers Exchange (FTGE) contention that, in 2006-2007, Florida tomato harvesters earned from $10.50 to $14.86, with an average wage of $12.46 per hour. Putting aside the fact that these hourly figures are not actual hourly wages paid, but rather earnings by the piece figured into hourly equivalents on the basis of unverified growers’ hours records… let’s take a closer look at this credulity-straining contention.

An average hourly wage of $12.46 translates into $24,920 per year for a typical hourly job based on a stable 40-hour work week, 50 weeks per year. Yet according to the US Department of Labor, farmworkers’ average yearly income in 2001 was only $7,500. That same report described farmworkers as “a labor force in significant economic distress,” citing farmworkers’ “low wages, sub-poverty annual earnings, (and) significant periods of un- and underemployment” to support its conclusion. The Department of Labor’s 2006 report showed a slight increase, up to $10,000-$12,000 per year, though the increase could be explained by the fact that the 2006 survey included manager and supervisor wages in the sample. Still, even the 2006 figures are less than half what the growers hourly figures would indicate.

Why the huge difference between the growers’ hourly estimates and the government’s objective annual figures? Because, as the Miami Herald article indicates, farmwork is a job with irregular hours, and the cost created by those irregular hours is entirely borne by the workers. Harvest not ready? Workers are out of luck. Business slow? Out of luck. Rain? Out of luck. Sick? Out of luck.

Why the huge difference between the growers’ hourly estimates and the government’s objective annual figures? Because, as the Miami Herald article indicates, farmwork is a job with irregular hours, and the cost created by those irregular hours is entirely borne by the workers. Harvest not ready? Workers are out of luck. Business slow? Out of luck. Rain? Out of luck. Sick? Out of luck.

Because in farmwork, even if work isn’t available, you still have to be ready and available for work, or you will lose your job when work does open up. But you don’t get paid when you’re waiting — just ask the guys from the Miami Herald article, who complained that they had “been in Immokalee for over two months and (had) yet to work anything close to a 40-hour week.” The article continued, “The growers say Sanchez and his co-workers will get more hours any day now, as soon as the season gets into full swing.”

That’s why hourly figures are meaningless when you can work 60 hours one week and 0 hours the next. And that’s why the growers always talk in terms of hourly wages – and never annual incomes – when defending themselves against claims of endemic farmworker poverty.

But what does this all mean if your goal is to raise farmworker incomes? You can’t change the nature of the harvest – crops ripen when they ripen, rain falls when it falls. But you can change the amount workers earn when they are working, and the way to do that is to raise the piece rate. Even if you can’t pick 2,000 hours a year as you might in a regular job, you can earn more when you are picking and end up with a decent income at the end of it all.

|

|

Photo by Nuri Valbona, Miami Herald staff

|

And that’s what the CIW has been calling for all along. Common sense: Farmworkers are poor. Work is irregular and piece rates have been stagnant for nearly thirty years. Increase the piece rate and you can increase incomes.

Blowback – Public reaction not favorable

Perhaps sensing that they would not win the battle against reality on the issue of farm labor wages, the growers have gone behind the scenes to game the odds in their favor. As revealed by the AP, the growers’ lobby instituted a $100,000 fine designed to make it financially difficult, if not impossible, for otherwise willing growers to participate in the Yum Brands and McDonald’s agreements.

While the FTGE’s Reggie Brown has called the CIW agreements “un-American,” the only thing that truly seems “un-American” in all this is the specter of a growers’ committee dictating to its members with whom they can and can’t do business. As Stephen Ross, a Penn State University law professor, said in the AP article, “(The FTGE) is limiting one way in which these growers can compete for the business of these major fast-food contracts,” said Stephen Ross, a Pennsylvania State University law professor. “The only antitrust violation I see is the growers’ response.”

Keva Silversmith of Burger King, quoted in an opinion piece by Robyn Blumner of the St. Petersburg Times (“At a penny per pound, a little adds up to a lot”), however, opined, “Florida growers have a right to run their business how they see fit.”

That answer didn’t satisfy the Times’ Blumner. She quizzed the FTGE’s Brown on the lobby’s contention that the CIW’s agreements are illegal:

“Reggie Brown, executive vice president of the exchange, refused to detail the specific legal objections, telling me to “pay for your own legal opinions.” He also refused to point me to a particular statute, suggesting I look at the fields of labor and antitrust law.

When I asked if the exchange was threatening growers with huge fines for participating in the penny agreement, he said that the exchange is “a private business enterprise that is not subject to public scrutiny,” and refused to answer.”

Needless to say, Blumner found the industry’s arguments unconvincing. She writes, “Consumers tend to respond well to a company they think is socially responsible, and the converse is true.” She ends her piece, “Okay, consumers, sic ‘em.”

Another opinion piece published on the occasion of Thanksgiving took a different cut at the resistance by Burger King and the growers to the Campaign for Fair Food. In an article published in several newspapers across the state, entitled “Today’s bounty didn’t pick itself,” Emily Eisenhauer of the Research Institute on Social and Economic Policy at Florida International University writes:

Another opinion piece published on the occasion of Thanksgiving took a different cut at the resistance by Burger King and the growers to the Campaign for Fair Food. In an article published in several newspapers across the state, entitled “Today’s bounty didn’t pick itself,” Emily Eisenhauer of the Research Institute on Social and Economic Policy at Florida International University writes:

“The problem is that the rate workers are paid for harvesting tomatoes has not increased significantly since 1978. No raises, no cost of living increases. Thirty years ago a dollar was worth three times what it is today, which means workers today must work three times as hard for the same pay. Growers say they are squeezed on both sides — by pressure from buyers to keep prices low and by rising production costs. So it’s the workers who get squeezed.

That’s why workers have turned to large fast food chains to demand a one-cent per pound pay increase. In 2005, YUM Brands and Taco Bell signed an agreement with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to raise farm workers’ pay and create a system where a third party will make sure the pay goes to workers. The agreement will also give workers a say in improving working conditions. Last April, McDonald’s signed a similar agreement, and now the pressure is on Burger King to sign. Eventually it will sign, and Florida farm workers will get their long overdue pay increase. The increase could raise a farm worker’s annual wages, currently at or below poverty, to nearly $19,000 per year, a living wage for the area of Immokalee.

This is certainly a step toward restoring the value and dignity of farm labor. But we need to rethink broadly the way we treat the people who harvest our food. Farm workers are treated differently from other workers in the letter of the law and in enforcement of laws, and that difference has meant declining status and conditions of farm work, to the point where it is commonly known as “work no one else wants to do.” Agricultural laborers were excluded from 1930’s labor reforms, which means they are not eligible for overtime and not allowed to unionize, and this lack of rights directly contributes to the poverty and insecurity farm workers face today.

The solution is in recognizing the interrelatedness of what we eat, where it comes from and how it affects our health, economy and society. No matter what kind of technology we develop in the future we will always need and enjoy food, especially fresh food. We need to bring farm work into the fold of valued and rewarded work, with protections to ensure our food is safe and abundant, and that the people who harvest it are treated with respect and dignity.”

Blind and still can’t see

This week began with the CIW crossing the Atlantic to accept the 2007 Anti-Slavery Award in London on the 200th anniversary of the passage of the Slave Trade Abolition Bill in the British Parliament. And we would end this update on one final reflection inspired by that horrific period of our history.

In 1748, overcome by a sudden and crippling awareness of the human suffering all about him while on his ship, the Greyhound, British slave ship captain John Newton experienced a profound conversion to Christianity. The hymn he penned to celebrate that conversion – Amazing Grace – has since become an anthem for people struggling for freedom and human rights around the world. Its first verse captures Newton’s epiphany:

“Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.”

In a 21st century reversal of John Newton’s conversion, Burger King executives have not only teamed up with the most conservative elements of Florida’s tomato industry to stand in the way of fundamental human rights for the state’s farmworkers, but have actually taken aggressive measures to reverse the gains already won by the Campaign for Fair Food through the CIW’s historic agreements with Yum Brands and McDonald’s.

Despite decades of exposes, scandals, and lawsuits revealing the systematic exploitation of Florida’s farmworkers – including six federal prosecutions for modern-day slavery in the past ten years alone – Burger King executives and their tomato industry partners are blind and still can’t see the glaring need for real reform in Florida’s fields. In the words of Burger King’s Keva Silversmith, “Florida growers have a right to run their business how they see fit.”

Worse yet, they have launched a full-out PR blitz to blind the public, as well.

Join us in Miami this Friday, November 30th, to let them know it isn’t going to work.