Susan L. Marquis, dean of the Pardee RAND Graduate School: “They’ve already been successful in a measurable way at effectively eliminating modern-day slavery and sexual assault, and greatly reducing harassment.”

NYT: “Over the last decade, [the Fair Food Program] has helped transform the state’s tomato industry from one in which wage theft and violence were rampant to an industry with the some of the highest labor standards in American agriculture.”

Last week, in our report on the unforgettable “March of the Red Carnations” at Ohio State University, we mentioned in passing that a blockbuster new article on the CIW’s Wendy’s Boycott had been published in the New York Times. This morning we have a moment – as students, faith leaders, Gainesville community members and farmworkers from Immokalee gather their forces for what promises to be a massive march later today on the University of Florida campus – to take a closer look at the Times article, an article so big that it took up nearly the entire front page of the Friday Business Section!

The report, by the New York Times labor reporter Noam Scheiber, covered a tremendous amount of ground, from refuting Wendy’s claims that greenhouse growers are somehow inherently socially responsible, to covering the growing momentum of student-led campaigns to kick Wendy’s restaurants off campus – backed by a new wave of city governments declaring their support for the students’ efforts in college towns from Ann Arbor, Michigan, to Gainesville, Florida.

Here below are several extended excerpts from Friday’s NYT report, but we strongly suggest that you read the article in its entirety at the Times’ website, which you can find here. And if you are reading this post and are in the Gainesville area, be sure to join us at the University of Florida’s Norman Field today at 12:30 for the kick off of the big march to President Fuch’s office!

March 7, 2019

A program created by a group that organizes farmworkers has persuaded companies like Walmart and McDonald’s to buy their tomatoes from growers who follow strict labor standards. But high-profile holdouts have threatened to halt the effort’s progress.

Now the group, a nonprofit called the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, is raising pressure on one of the most prominent holdouts — Wendy’s — which it sees as an obstacle to expansion.

The Immokalee workers’ initiative, called the Fair Food Program, currently benefits about 35,000 laborers, primarily in Florida. Over the last decade, it has helped transform the state’s tomato industry from one in which wage theft and violence were rampant to an industry with the some of the highest labor standards in American agriculture.

“They’ve already been successful in a measurable way at effectively eliminating modern-day slavery and sexual assault, and greatly reducing harassment,” said Susan L. Marquis, dean of the Pardee RAND Graduate School in Santa Monica, Calif., who has written a book on the program. “Pay is substantially higher for these people.”

***

Under the Fair Food Program, buyers like Walmart and McDonald’s agree to pay 1 to 4 cents more per pound of tomatoes. The growers, in turn, agree to pay farmworkers at least the local minimum wage, to which the premium adds a bonus, and to meet a set of labor standards like providing shade and water for workers and ensuring freedom from physical and sexual abuse. Some of the practices are required by law but flouted on many farms.

Heidi Schauer, a Wendy’s spokeswoman, said in an email that the company required its tomato suppliers to submit to third-party reviews of their human rights and labor practices. She said the chain had recently committed to buying all of its tomatoes from indoor greenhouse farms, most of them in the United States and Canada, which “strengthens our commitment to treat people with respect.”

Several experts questioned the value of such reviews, which are often superficial, as well as the suggestion that greenhouse farms provide more humane work environments.

“Indoor greenhouse farms are not inherently better in terms of labor conditions,” said Margaret Gray, an associate professor of political science at Adelphi University who has studied farm labor conditions.

***

In recent weeks, activists affiliated with the Immokalee workers have stepped up pressure at several universities for Wendy’s to sign on to the Fair Food Program.

The effort borrows its strategy from a campaign that student activists connected to the Immokalee workers waged against Taco Bell. Over nearly four years, supporters on several campuses persuaded officials to either remove the chain from campus or block it from doing business there in the future. In 2005, Taco Bell’s parent company agreed to buy its tomatoes through the program, becoming the first major company to sign on.

Like Taco Bell, Wendy’s is potentially susceptible to protests on college campuses. A significant number of Wendy’s customers are in their teens and 20s, according to Mark Kalinowski, an industry equity analyst.

***

One recent focus of the campaign against Wendy’s is the University of Michigan, where, according to a statement from the company in late January, its campus franchisee has chosen not to seek to renew its lease.

Wendy’s later said the franchisee had made the decision a few years ago. But the announcement came just before the local City Counciland the university’s student government passed resolutions advocating boycotts of Wendy’s.

Last week, the Board of Aldermen of Carrboro, N.C., a town near the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, passed a resolution urging Wendy’s to join the Fair Food Program. And the mayor of Gainesville, home to the University of Florida, has placed a similar resolution on the agenda of a City Commission meeting this week.

In an interview, the mayor, Lauren Poe, said that he intended the resolution as a way of supporting farmworkers, not opposing the university, but that he hoped the school would ban the Wendy’s that operated on campus until the company joined the Fair Food Program.

***

Unless more companies commit to buying tomatoes through the Fair Food Program, growers who haven’t joined will continue to have a market for their products and may not feel pressure to raise their labor standards.

“I’m sure there are people that look at all of us who did join the program and viewed it as an opportunity to go do business with brands that didn’t want to sign up,” said Jon Esformes, chief executive of Sunripe Certified Brands, which grows tomatoes in Florida, Georgia and Virginia.

Sunripe agreed to join the program in 2010. Like other growers in the program, it must show new workers a video about their labor rights and let the Immokalee group provide education sessions for workers at least once per season. Workers are urged to report abuses to a 24-hour hotline, which is monitored by an independent council that investigates complaints.

The council also regularly audits farms for compliance. Fair Food auditors interview at least half the workers on a farm — often hundreds of them — which is far more than conventional auditors typically interview. Growers found to have violated the program’s code of conduct can lose access to buyers.

The stakes go far beyond tomatoes. In the coming years, the Immokalee workers hope to bring their model to a variety of crops in many states, where tens of thousands of workers are still vulnerable to abuses.

Be sure to check out the article in its entirety here.

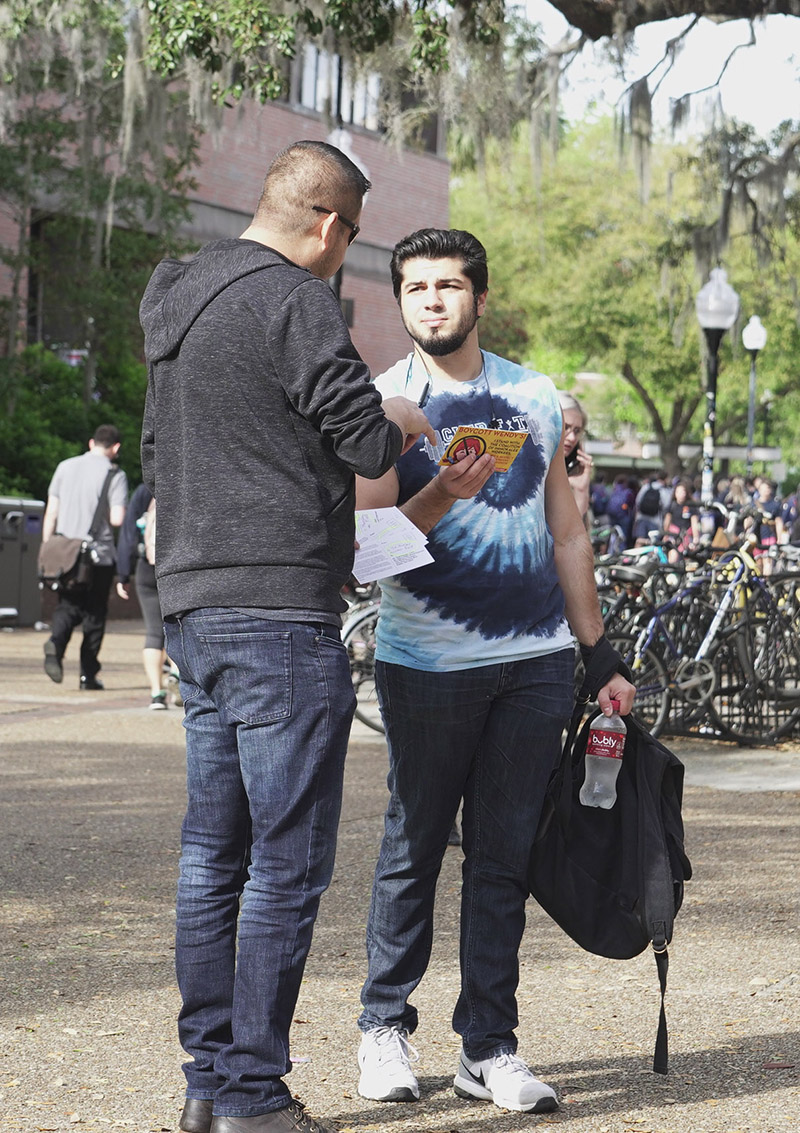

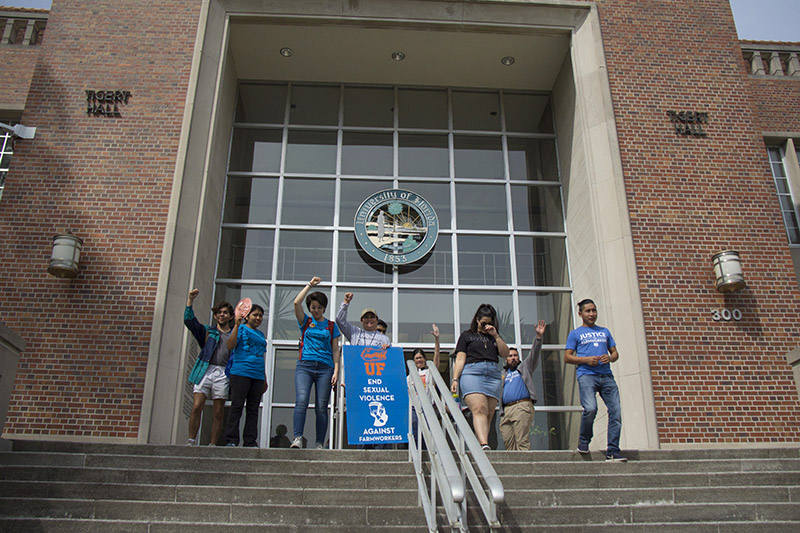

Finally, to get you inspired for today’s march, we have a bonus video and photo gallery from the first two days in Gainesville, which included a beautiful sunny picket, a powerful delegation to the offices of President Fuchs, flyering across UF’s sprawling campus, a reflection and some birthday fun at Lake Wauburg, and last night’s vigil on the steps of the UF administrative building. We hope to see you at the march today in Gainesville!