10-year, independent study by NGO MSI Integrity finds corporate-led, Multi-stakeholder Initiative (MSI) model for social responsibility “should not be relied upon for the protection of human rights”;

Study concludes: “MSIs are not effective tools for holding corporations accountable for abuses, protecting rights holders against human rights violations, or providing survivors and victims with access to remedy”;

Study cites Fair Food Program, Worker-driven Social Responsibility model as leading examples of new “gold standard,” with effective mechanisms for “empowering rights holders to know and exercise their rights”…

PLEASE SHARE:

-

A decade of research from @MSIIntegrity finds systemic failures across 40 multi-stakeholder initiatives, calls @FairFoodProgram, #WSR Model the “gold standard” for “empowering rights holders to know and exercise their rights” bit.ly/3eicw8o

-

If the #BizHumanRights & #CSR communities want to protect the rights of workers & communities, #MSIs are not the answer – @MSIIntegrity. Rights holders & communities must be in charge of the businesses that impact them. bit.ly/3eicw8o #RethinkMSIs #BeyondCorporations

-

A decade of research from @MSIIntegrity finds systemic failures across 40 multi-stakeholder initiatives: Weak standards, limited access to remedy, poor detection & compliance mechanisms. MSIs are #NotFitForPurpose to protect human rights. bit.ly/3eicw8o

Summary:

An extraordinary report released last week — the product of a decade of study and analysis of 40 international standard-setting programs, conducted by the Institute for Multi-Stakeholder Initiative Integrity (“MSI Integrity”) — concluded that the Multi-stakeholder Initiative model, the dominant paradigm for corporate social responsibility since the 1990s, has resoundingly failed at its primary objective: protecting human rights in global supply chains. To meet the still urgent need for effective human rights protections, the report calls for approaches that situate workers and communities “at the center of decision-making” and that endow those “rights holders” with real power to enforce their own rights. The study points to the Fair Food Program in the food industry, and the Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR) model more broadly, as leading examples of proven — and demonstrably superior — alternatives to the failed MSI model.

The report was published by MSI Integrity, a non-profit organization incubated a decade ago at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic and “dedicated to understanding the human rights impact and value of voluntary multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) that address business and human rights.” The study looked at a wide range of MSIs in multiple sectors — including the Equitable Food Initiative (EFI), Fair Trade International, and the Rainforest Alliance in the food industry — and concluded that their lack of effective mechanisms “to center the needs, desires, or voices of rights holders,” and failure to address “the power imbalances that drive abuse,” prevented the voluntary, corporate-led social responsibility programs from realizing their claims of effective human rights protection. Among other specific deficits, the study found serious shortcomings in the audit processes of the MSIs investigated, a lack of effective grievance mechanisms and of meaningful consequences for violations, as well as the failure to make public the suspension of suppliers determined to be out of compliance.

In other words, the study concluded that all social responsibility programs are not created equal — that there are real differences between the dominant, corporate-led paradigm of social responsibility and the WSR model, differences not only of philosophy and of mechanisms, but of outcomes, as well. Indeed, MSI Integrity’s groundbreaking research confirms what tens of thousands of farmworkers, and counting, know from lived experience: The Fair Food Program’s unique mix of worker-driven monitoring mechanisms and market consequences for human rights violations is, in fact, more effective than other competing programs at addressing, and ending, long-standing abuses in corporate supply chains.

A look back at the origins of the Fair Food Program: “Taco Bell makes farmworkers poor!”…

Nearly twenty years ago, farmworkers with the CIW in Immokalee had run into a brick wall. Their struggle to end the grinding poverty, systemic wage theft, and widespread violence that had plagued Florida’s fields for generations, and to demand a voice in the decisions that shaped their lives, had made only marginal progress toward the more modern, more humane agricultural industry they envisioned. No matter what the CIW did — for the better part of a decade, workers in Immokalee organized powerful and dramatic protest actions, including community-wide strikes, marches and even a 30-day hunger strike calling for “dignity, dialogue, and a fair wage” — the growers remained fiercely opposed to change. Even several high-profile modern day slavery prosecutions failed to put a dent in the growers’ resistance.

That’s when the CIW realized that the growers and their farm bosses weren’t, in fact, solely responsible for the poverty and humiliation workers faced in the fields, that other, more powerful forces played a significant role in their exploitation, as well: the massive, multi-billion-dollar retail food brands that bought and sold the produce they picked. By leveraging their unprecedented purchasing power, those fast-food brands and grocery chains were able to demand lower and lower prices at the farm level, a demand the growers were effectively powerless to refuse. In turn, the growers’ shrinking margins created a strong and ever-increasing downward pressure on wages and working conditions in the fields, resulting in the poverty and abuse that gave rise to the CIW in the first place.

In the words of the slogan that launched the Campaign for Fair Food in 2001, workers in Immokalee realized that “Taco Bell makes farmworkers poor!” And they wagered that the same overwhelming purchasing power that helped drive their poverty could be leveraged to help improve farmworkers’ incomes and compel compliance with more humane standards, if they could mobilize consumers to support their demands. For the next decade, workers from Immokalee criss-crossed the country to build a nationwide network of allies demanding “Fair Food,” food harvested in compliance with a still aspirational code of conduct designed by the CIW and drawn from twenty years of struggle. Ten years later, in 2011, the Fair Food Program (FFP) was launched, endowed with the power of nearly a dozen, legally-binding Fair Food agreements with some of the world’s largest retail food corporations that conditioned those companies’ tomato purchases on compliance with the standards set out in the CIW’s new code.

To be clear, those buyers already had, without exception, existing supplier codes of conduct. But what they didn’t have was a demonstrable history of enforcement of the standards contained in those codes in the fields where workers throughout Florida harvested their tomatoes. Indeed, the very existence of the CIW itself, sparked to life by workers no longer willing to suffer abject poverty and abuse without recourse to justice, was tangible evidence of the utter failure of those corporate codes and any associated monitoring efforts. And the Fair Food Program was the workers’ plan for closing the gap between the brands’ promises of human rights protections and their own lived reality of widespread abuse. By creating humane harvesting standards informed by that reality, educating workers about their rights with the goal of creating an army of worker/monitors across the vast Florida tomato industry, and harnessing the participating buyers’ purchasing power to enforce those rights when they were violated, the CIW launched the first and most comprehensive example of a new paradigm for protecting human rights in global supply chains that would come to be known as Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR).

Standards without enforcement…

At just about the same time that the CIW was launching the groundbreaking Fair Food Program in Florida — born of the fact that the human rights standards promised in the buyers’ codes of conduct were going almost uniformly unenforced, and predicated on the idea that enforcement is only possible when workers themselves take a leading role in defining and monitoring their own rights, backed by the market power of the industry’s largest buyers — a process designed to evaluate the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility efforts was being launched at the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard University’s Law School.

And now, a decade later, the results are in. In the words of the organization that undertook that evaluation process, MSI Integrity:

For the past decade, MSI Integrity has investigated whether, when and how multi-stakeholder initiatives protect and promote human rights. The culmination of this research, detailing the significant limitations of MSIs, is available in our report Not Fit-for-Purpose…

When MSIs first emerged in the 1990s, they appeared to offer a transformative and exciting proposition. For years human rights and advocacy organizations had been investigating and naming-and-shaming companies for their connections to sweatshop labor, deforestation, corruption, and other abusive behavior. As this advocacy grew louder—and as government regulation of corporations remained elusive—a new experiment began. Rather than being barred from boardrooms, some large civil society organizations began working alongside businesses to draft codes of conduct, create industry oversight mechanisms, and design novel systems of multi-stakeholder governance that aimed to protect rights holders and benefit communities.

These international standard-setting MSIs rapidly proliferated. By the 2000s, they had become a “gold standard” of voluntary business and human rights initiatives, encompassing everything from freedom of expression on the internet to the certification of palm oil as “sustainable.” Within two decades—and with minimal critical examination into its effectiveness or wider impacts—multi-stakeholderism had evolved from a new and untested experiment in global governance into a widely accepted solution to international human rights abuses.

But have MSIs delivered on their promise to protect human rights?

After reflecting on a decade of research and analysis, our assessment is that this grand experiment has failed. MSIs are not effective tools for holding corporations accountable for abuses, protecting rights holders against human rights violations, or providing survivors and victims with access to remedy. While MSIs can be important and necessary venues for learning, dialogue, and trust-building between corporations and other stakeholders—which can sometimes lead to positive rights outcomesthey should not be relied upon for the protection of human rights. They are simply not fit for this purpose… read more

The report goes on to identify two key shortcomings common to the MSI programs investigated in the study:

… Two features have intrinsically limited the capacities of MSIs to protect rights. First, MSIs are not rights holder-centric. In general, MSIs employ a top-down approach to addressing human rights concerns, which fails to center the needs, desires, or voices of rights holders: the people whose living and working conditions are the ultimate focus of MSIs, whether they are farm workers, communities living near resource extraction sites, or internet users. Our research and experiences have shown that there is little meaningful emphasis in MSIs on empowering rights holders to know and exercise their rights, or to directly engage in the governance or implementation of initiatives. Centering rights holders is essential, however, for the efficacy of any initiative that purports to address human rights. Rights holders hold critical information for ensuring that standard-setting and implementation processes respond to their lived experiences. For example, what rights issues and remedies are of greatest importance to be addressed? What sort of whistleblower protections or oversight systems are needed for people to feel safe reporting alleged abuse? Are interventions actually working? Top-down approaches risk failing to harness the knowledge or trust of those whose lives or rights are at stake.

Second, MSIs have not fundamentally restricted corporate power or addressed the power imbalances that drive abuse. Companies have preserved their autonomy and safeguarded their interests throughout the design, governance, and implementation of MSIs. The mechanisms most central to rights protection, such as systems for detecting or remediating abuses, have been structurally weak. This has meant that MSIs are capable of achieving positive outcomes where there is genuine commitment on the part of corporate members to change; however, when that goodwill breaks down—as it often has—MSIs have been able to do little to protect human rights… read more

Given the study’s analysis of the MSI model’s shortcomings, it is hardly surprising to see what social responsibility model MSI Integrity identifies as the way forward for real, measurable human rights protection:

… [O]ther forms of private governance are spreading and may be displacing the role of MSIs. One important development is the emergence of the Worker-driven Social Responsibility (WSR) model through the WSR Network, which presents itself as both a counterpoint and response to the failings of MSIs and other voluntary corporate codes of conduct by creating legally enforceable obligations for companies that join. This model has been widely celebrated and acclaimed. For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on human trafficking called the Fair Food Program (FFP), one of the earliest examples of a WSR initiative, an “international benchmark”; a representative from the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights noted that it was a “groundbreaking model” that they hoped “serves as a model elsewhere”; and an article in the New York Times described it as the “best workplace-monitoring program” in the United States. Since FFP was launched in 2011, other WSR initiatives have emerged—the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (2013); the Milk With Dignity Agreement (2017); and the Gender Justice in Lesotho Apparel agreement (2019)—and have garnered wide support among CSOs and unions. This level of acclaim and growth indicates that MSIs appear to no longer be the “gold standard” of private governance.

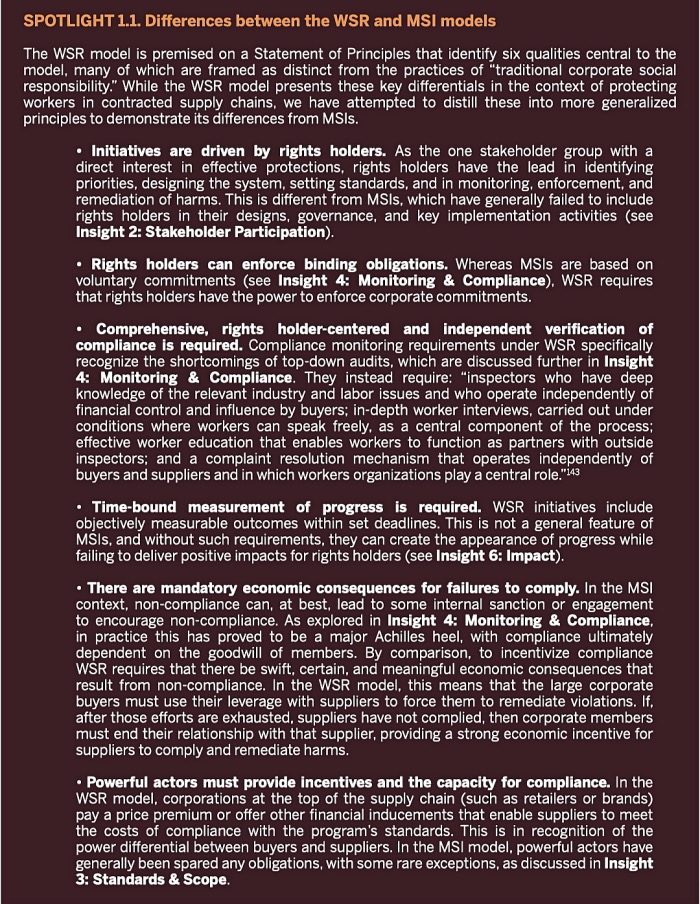

An overview of the main differences between the MSI and WSR models is presented in Spotlight 1.1; however, two fundamental distinctions are that the WSR model: (1) is structurally designed to center rights holders in the monitoring and implementation of standards; and (2) creates legally binding standards that workers can enforce outside of the initiatives. The importance of these two qualities was emphasized in a statement by 15 CSOs supporting WSR, including the American Civil Liberties Union, Human Rights Watch, and the Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic. The statement underscored the importance of enforceability and noted that the level of worker participation envisaged by WSR “is not only required by human rights standards . . . but is essential for the efficacy of any initiative to improve workers’ rights in the supply chain.” 139 The statement concluded that “WSR models overcome the shortcomings of alternative approaches in protecting workers’ basic dignity and human rights to fair working conditions, health, and safety.”

The rise of the WSR model as a more rigorous private governance alternative not only threatens to displace MSIs’ perceived legitimacy as the “gold standard,” but it also has reignited the debate about whether MSIs are human rights maximizing and seriously dulled the aura of legitimacy surrounding MSIs as a governance miracle… read more

The report even includes a neatly summarized chart of the key differences between the MSI and the WSR models:

We highly recommend this unprecedented, in-depth, longitudinal study of one of the most urgent issues in the global human rights movement today, the protection of workers’ and communities’ fundamental human rights at the bottom of corporate supply chains. You can find the report here.

In conclusion…

In the decade since MSI Integrity launched its study, the CIW has brought the Fair Food Program to scale, expanding it to new states and new crops from its base in the Florida tomato industry. At the same time, the CIW and its partners in the Worker-driven Social Responsibility Network have collaborated in the replication of the broader WSR model on three continents and in multiple industries. In every instance of expansion and replication, new workers have seen the concrete benefits of the model’s worker-driven monitoring mechanisms and market-backed enforcement.

This exciting new study underscores the unprecedented effectiveness of the the Fair Food Program, and the urgency of the need to expand the broader WSR model to millions of workers in industries across the globe. The evidence is clear, yet far too many corporations remain slow to recognize the model’s unique efficacy, and continue to partner with, and invest in, the dozens of demonstrably ineffective MSI programs in agriculture, apparel, and other key industries. MSI Integrity’s study provides the long-overdue data and analysis necessary for any supply chain manager seeking to partner with the most ethical approach to protecting workers’ human rights. Now is the time for those corporations to commit to real social responsibility, and this remarkable new study points the way.