Terrifying brutality of Nicolas Morales’s death at the hands of the police — deemed “legally justifiable” by the State Attorney — cannot be allowed to stand…

Justice for Nicolas, deep and lasting reform for the community, must be done.

Nicolas Morales Besanilla is dead, killed by Corporal Pierre Jean of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office.

That’s the who and the what of it. He was killed on a quiet street in Farmworker Village just outside of Immokalee, in the early morning of September 17, 2020. That’s the where and the when.

Those are all the settled facts, simple, straightforward. Only the why remains in dispute. And it’s the why that will either drive deepening conflict, or bring about justice, and long-overdue change.

We now know, nearly five months to the day after Nicolas was killed, what the State Attorney thinks about why Nicolas was killed. The State Attorney’s Office announced last Friday that it would not seek charges against Cpl. Jean for killing Nicolas. According to the official press release, the killing was “legally justified.” Why? Because the video from the deputies’ patrol car dash cameras appears to show Nicolas trying to run from the police and then turn, for the briefest of moments, in the direction of Cpl. Jean while holding a pair of pruning clippers in one hand. That momentary turn was, apparently, all it took to justify Cpl. Jean’s decision to take Nicolas’s life, from the State Attorney’s point of view. That subtle shift of Nicolas’s shoulders, from parallel to Cpl. Jean toward the perpendicular, was, according to the State Attorney, enough to cause reasonable fear and, so, in the eyes of the law, justify Cpl. Jean’s split-second decision to kill Nicolas Morales.

But the State Attorney’s decision seems more an assessment born of necessity and stripped bare of context — a purely mechanical, heartless reading of events leading to a pre-determined conclusion — than the considered analysis of a complex tragedy involving multiple decision points, all leading inexorably toward a terrible conclusion, leaving one man dead, his son orphaned, and a community in crisis.

One crucial bit of context absent from the State Attorney’s statement: Nicolas Morales’s death was entirely, and indisputably, preventable. It is clear from the video that Cpl. Jean failed to assess Nicolas’s mental state, failed to communicate effectively with Nicolas, and consistently made decisions and took actions that escalated the situation and obviated less lethal means of control, turning an otherwise-possible peaceful resolution into a deadly one. Those multiple failures to assess and deescalate the scene that night put Cpl. Jean and Nicolas on a spiraling collision course that ended, 13 seconds later, in Nicolas’s death.

And when the death of one human being at the hands of another is preventable, except for the actions of the killer, then the killing, quite simply, cannot be deemed justifiable.

To truly know why Cpl. Jean fired four bullets at Nicolas Morales at close range, just seconds after arriving on the scene, the video demands a more thoroughgoing analysis:

***********************************

WARNING: The raw dash cam footage from police patrol cars in the video above contains moments that are graphic and truly devastating to watch.

The worst decision, every step of the way…

People with mental health issues are 16 times more likely to be killed in encounters with the police. Nicolas was clearly experiencing a mental health crisis on the night he was killed by Cpl. Jean. The call into the 911 operator described a person banging on random doors demanding to be let in, grabbing garden tools, and growing increasingly disturbed. And Nicolas’s agitated state when the Cpl. Jean and his fellow officers arrived on the scene should have been obvious to anyone, let alone a police officer who was (or if he wasn’t, should have been) trained in proper de-escalation techniques. Alone in the middle of the night, no shirt, no shoes, carrying garden tools and acting erratically, Nicolas presented a classic case study in mental health crisis.

In the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, Collier County Sheriff Kevin Rambosk told concerned citizens and Collier County Commissioners that his department had made dealing effectively with residents with mental health issues a priority, including securing training for CCSO personnel in a widely-respected crisis management approach known as the “Memphis Model.” From the Naples Daily News:

… Rambosk said the Sheriff’s Office has trained personnel to help those in crisis and get them to a location that can help them.

“We are one of the only law enforcement agencies that have this many trained, 40-hour Memphis Model (Crisis Intervention Team) trained, law enforcement officers,” he told commissioners.

Community members with mental health crisis [sic] should not be in jail and Collier’s jail population has been “significantly” reduced over the past decade, Rambosk said. read more

Yet, despite the CCSO’s emphasis on crisis intervention and de-escalation, from the first moments after the call came in to the 911 operator, to the last, tortured moments of Nicolas’s life, the people paid to protect the people of Immokalee did the wrong thing, each step of the way.

Dispatch: The Memphis Model includes training for dispatchers on how to recognize a call that involves a mental health crisis, including appropriate questions to ask to help determine whether to send an officer trained in crisis intervention (a “CIT officer”) to assist. According to the State Attorney’s report and the 911 transcript, the residents who ultimately called 911 that night first called the CCSO’s non-emergency number, and only called 911 when Nicolas began to grow increasingly agitated and bang on their door. As the caller described Nicolas’s erratic behavior, asking out loud at one point “Is he drunk?,” indicating unusual behavior, the dispatcher failed to ask any further questions that might help shed more light on his mental state. While we cannot know for sure, it appears from the records that the dispatcher failed to flag this incident as a mental health crisis.

Before Arrival: There is no evidence in the video that Cpl. Jean and his fellow officers communicated with each other on a plan for approaching the scene in advance of their arrival. Despite the erratic behavior conveyed by the dispatcher, and the fact that Nicolas is identified as an “Hispanic male,” there is no indication that the officers took time on the way to coordinate their approach or to prepare for encountering a Spanish-speaking man potentially experiencing mental health issues, only silence.

While effective preparation, from dispatch to pre-planning, is essential to successful crisis intervention, it is what happens at the scene that ultimately decides the fate of all those involved, suspect and officer alike. De-escalation training typically emphasizes “effective communication” and teaches officers the CAF (Calm/Assess/Facilitate) Model:

“Calm: to decrease the emotional, behavioral, and mental intensity of a situation;;

Assess: to determine the most appropriate response as presented by the facts

Facilitate: to promote the most appropriate resolution based on an assessment of the facts presented.” read more

De-escalation training emphasizes the use of techniques intended to reduce tension, instructing officers to: “Maintain safe distance… Use relaxed, well-balanced, non-threatening posture… Present self as a calming influence… Be aware that uniforms/tools can be intimidating.” It encourages officers to “use empathy and consider, ‘What if this person in crisis were a member of my family?'”

The approach follows a simple logic: When confronted with an individual potentially experiencing a mental health crisis, “If you take a LESS authoritative, LESS controlling, LESS confrontational approach, you actually will have MORE control.” (emphasis in the original)

Upon Arrival: Upon arriving at the scene, Cpl. Jean immediately takes the lead, exiting the patrol car and moving quickly toward Nicolas, who stands roughly 50 feet away. Within seconds of his arrival — and without consulting his partners or taking any time for an effective assessment — Cpl. Jean yells at Nicolas in English, telling him “Don’t come over here” and instructing him to “get on the ground.” He repeats his order several more times, each time more loudly, despite the clear evidence that Nicolas does not understand what he is being told to do. By yelling his commands, in English, at an increasing volume, Cpl. Jean failed to communicate effectively, raised the tension level from the very start, and established a dynamic where Nicolas was not complying with his directions, rather than establish himself as a calming presence and bring the situation under control.

At the same time that he is quickly closing the distance between himself and Nicolas and yelling his instructions in English without effect, Cpl. Jean decides to pull his service revolver and point it at Nicolas. No more than three seconds — three — after exiting his vehicle, Cpl. Jean reaches for his gun — not the less-lethal option of his taser — and aims it at Nicolas, prepared to kill. Cpl. Jean’s decision to leap directly to the threat of lethal force and aim his gun at Nicolas escalates the conflict immeasurably, pushing all involved to the edge of a precipice from which they will not return.

Shooting: Despite Cpl. Jean’s increasingly aggressive and threatening behavior — yelling, quickly closing the distance, pulling and aiming his gun — Nicolas continues to walk, in a demonstrably erratic, but non-threatening manner, in the direction of Cpl. Jean and his fellow officers, who now are approaching Nicolas from Cpl. Jean’s right and left, with a revolver and a police K-9, respectively. As Nicolas reaches the back end of a car parked at the end of the driveway, he gestures briefly as if in conversation, turns to his left, and then picks up his pace, beginning to jog on a path parallel to the approaching officers. In the process, Nicolas drops the shovel he had been carrying and moves apparently to run away, though he is effectively corralled by the three officers and never moves faster than a slow jog. At that moment, several non-lethal options remain available to the officers, despite the dangerous escalation provoked largely by Cpl. Jean’s actions.

Those non-lethal options would never be deployed, however. Below is a still image from the video showing the precise moment when Cpl. Jean (middle) fires his first shot at Nicolas. Three more would follow in quick succession:

Nicolas is still not fully turned in Cpl. Jean’s direction. Cpl. Jean stands the closest to Nicolas, having closed in on him. In contrast, the officer on Cpl. Jean’s right is beginning to back up as Nicolas approaches and has lowered his weapon, appearing to be reaching for a non-lethal weapon holstered on his left hip (he would say later in a written statement that “he holstered his weapon after seeing [Nicolas] drop the shovel in preparation for physical confrontation”). The officer with the K-9 still has not released the dog when Cpl. Jean fires his first shots.

Though both Cpl. Jean and the officer to the right had their service weapons pulled, only Cpl. Jean moves into Nicolas’s path, continuously aims squarely at him, and pulls the trigger. In contrast, the officer on the right lowers his weapon and moves backward as Nicolas approaches. The officer on the left, armed with a K-9 presumably trained specifically for bringing suspects into submission, doesn’t release his dog until after Cpl. Jean fires his weapon. By choosing to close aggressively on Nicolas and shoot at him four times at close range — rather than retreat, contain, and control him — Cpl. Jean sealed Nicolas’s fate.

Aftermath: Despite the horrifically callous, senseless nature of Nicolas’s death, what happened in the minutes following his shooting are even, somehow, harder to watch. Immediately following Cpl. Jean’s decision to shoot Nicolas, the officer on his left looses his K-9, which pounces on Nicolas, who has fallen, helpless and unarmed, to the ground. The dog sinks its teeth into Nicolas’s shoulder. As he lay dying on the ground, Nicolas is mauled by the police dog, which is allowed, uninterrupted by his handler, to bite and tear at Nicolas’s shoulder for nearly 20 seconds, then refuses to release Nicolas from his grip for another 40 seconds as his handler tries, and fails, to bring the dog under control. All the while, Nicolas cries out, moans, and calls for his mother. Cpl. Jean keeps his gun trained, pointlessly, on the fallen, mauled, unarmed, wounded and dying Nicolas, and the third officer turns and runs for first aid. It is a scene of unforgettable cruelty, incompetence, and suffering, demonstrating an astounding lack of empathy, most notably on the part of Cpl. Jean, who appears — as he has from the very outset — dangerously married to his service revolver, unable to relate to the world around him except from behind its sights.

Conclusion…

The State Attorney concluded that Cpl. Jean killed Nicolas Morales because he felt threatened by Nicolas’s behavior and, therefore, that his decision to shoot Nicolas was legally justified. But that reduces a long and complex sequence of decisions and actions down to just two of its links, ignoring the chain of cause and effect by which Cpl. Jean led four people to the edge of a cliff, and ended with one of them lifeless on the rocks below.

Others, after watching and re-watching the gut-wrenching videos, will surely disagree with the State Attorney’s conclusion, and offer alternative explanations. Some may say that Cpl. Jean failed to see Nicolas as a human being, that, for whatever reason, he was able to dehumanize Nicolas so much that he could kill him with what appeared to be little more thought than it might take to kill a cockroach that surprised you in the night. Like Nicolas’s subtle turn in the direction of the police, Cpl. Jean’s utter disregard for human life that night was also clearly visible in the video. In fact, most would say more so.

Some may say it was Cpl. Jean’s military training kicking in — he appears to have served in Afghanistan — his time serving in the Army perhaps overwhelming his police training in the heat of the moment and causing him to see Nicolas as an enemy combatant, to close in on him, give him no quarter and shoot him dead all within seconds of arriving on the scene, instead of seeing him as a man who was clearly troubled, lost, and alone in the middle of the night, a father of a young boy, a fellow citizen to serve and protect.

And still others may think it was simple incompetence, that Cpl. Jean proved himself that night to be a man who never should have been trusted with the power to kill, who found himself in a moment too big for him, causing him to react instead of think, his finger to jump, instead of remain safely off the trigger (or, better still, on the taser instead) while he cooly managed an ordinary crisis and brought Nicolas to safety, and back to his son, also alone, scared and waiting for his father to come home.

In the end, we may never know the exact explanation for Cpl. Jean’s actions that night. But we do know this: from when he put his first foot on the ground in Farmworker Village that night as he exited his patrol car, to when he put three bullets into Nicolas’s body from close range, he violated virtually every single principle and method of the state of the art de-escalation training he should have received as a road patrol officer with the CCSO. In a podcast from 2020, Collier County Sheriff Kevin Rambosk explains the importance of the “Memphis Model” for training officers how to recognize the signs of a mental health crisis and to de-escalate situations where mental health is an issue, and why he made it a mandatory training for all road and jail deputies. Click on the file below to listen to three minutes of that podcast:

We agree with Sheriff Rambosk that training in the Memphis Model is an excellent start to more ethical, more empathetic, and more effective policing. But while training is certainly necessary, it is clearly not sufficient. The story of Nicolas’s death is a story of failure at every level — management, training, policing. If you believe that police officers can prevent unnecessary deaths through the effective practice of de-escalation training, then you must also believe that when they violate every aspect of those life-saving procedures and escalate a situation that ends needlessly in death, those officers bear significant responsibility for that death and must be held accountable.

Cpl. Jean was taken off the street after shooting Nicolas Morales, but just one week later, he was back on duty. Today, in the wake of the State Attorney’s decision, Cpl. Jean is not only walking the streets again with the power to kill, but effectively exonerated for his killing of Nicolas just five months ago.

The State Attorney’s blindered decision not to press charges for the killing of Nicolas Morales cannot stand.

The CCSO’s decision to return Cpl. Jean to the streets after demonstrating a callous, dangerous indifference to human life cannot stand.

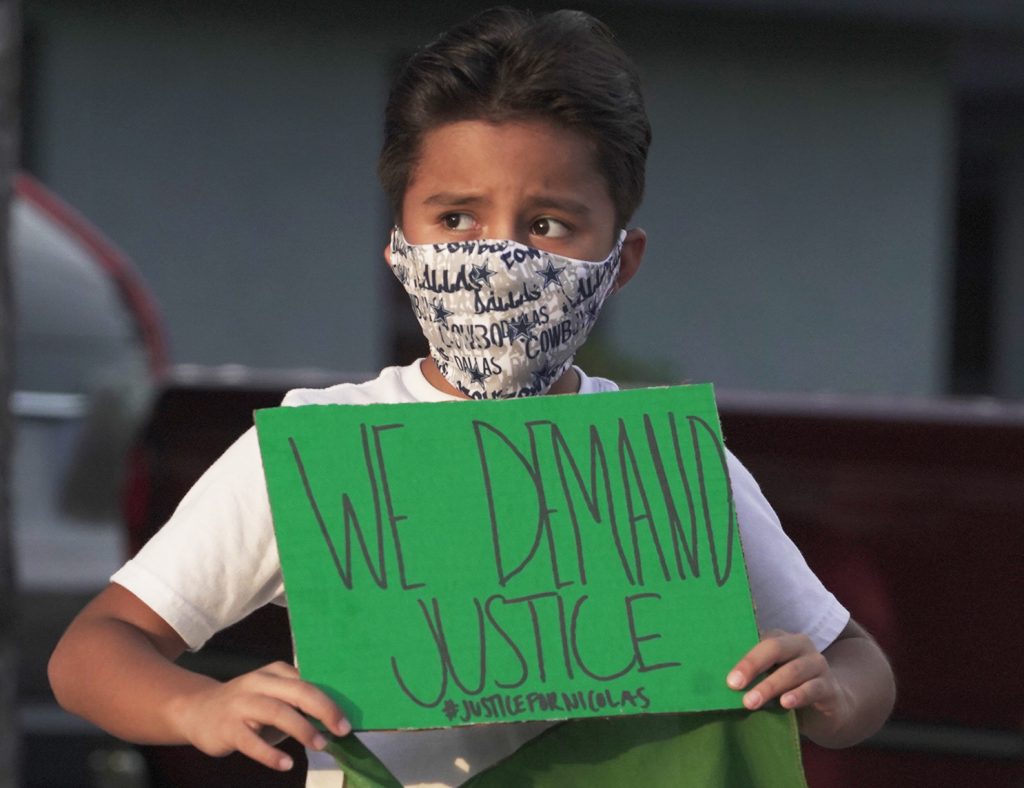

For Nicolas Morales Jr. — an orphan today, his mother lost to illness, his father to police violence — nothing can be done to fill the hole left by his father’s loss. But something must be done to protect him, and lift him up, as he makes his way through life without his father’s loving hand to guide him. And for the Immokalee community as a whole, real, lasting police reform — with accountability, transparency, adequate measures to protect those in mental health crisis from needless death, and meaningful community participation — is a must. And to get there, to a world where police violence in Southwest Florida is a thing of the past, like forced labor and sexual violence in the Fair Food Program, will require consciousness, commitment and, like any significant change, relentless hard work.